Executive Summary

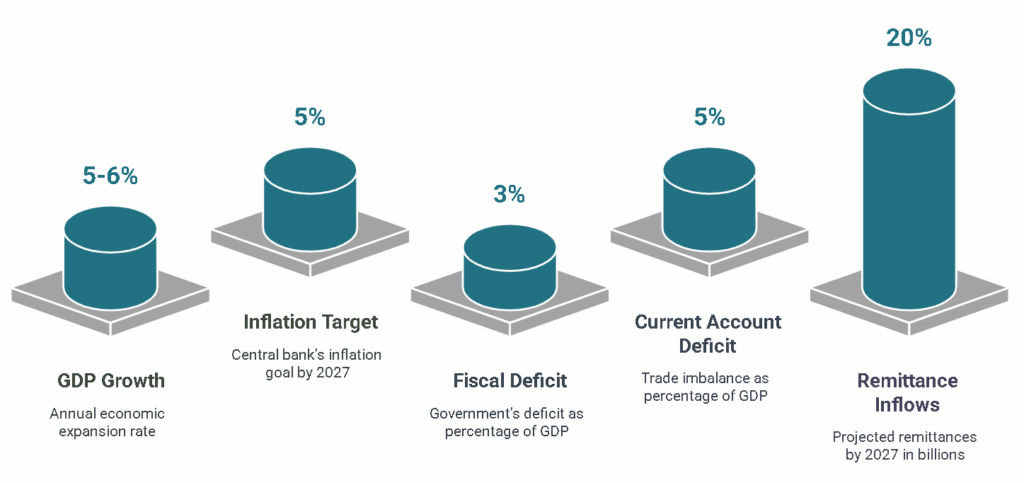

Uzbekistan is poised for robust economic growth through 2030, underpinned by ongoing market reforms and regional integration efforts. Real GDP is forecast to expand around 5–6% annually, enabling the country’s economy to potentially double in size to nearly $200 billion by 2030 5. Inflation is on a downward trajectory—from about 10% in 2024 toward the central bank’s 5% target by 2027 5—reflecting prudent monetary policy. The government is containing fiscal deficits below 3% of GDP and aims to achieve an investment-grade sovereign credit rating by the end of the decade 5. External balances will remain manageable: while imports still exceed exports, rising gold and diversified exports alongside sustained remittance inflows (projected to reach $20 billion by 2027 3) should keep the current account deficit near 5% of GDP 8. Foreign direct investment (FDI) is accelerating, especially from Asian partners, reflecting improved business conditions and investor confidence.

Beyond macroeconomic forecasts, Uzbekistan faces a critical geopolitical balancing act. The nation’s foreign policy under President Shavkat Mirziyoyev has embraced a “multi-vector” approach, seeking positive ties with Russia, China, and the United States while preserving national autonomy. Managing relations with these major powers is essential for economic resilience: Russia remains a key security partner and destination for Uzbek migrant labor, China has become Uzbekistan’s largest investor and trading partner 7 en.people.cn, and the U.S. is courting Tashkent as a strategic partner in Central Asia 4. Simultaneously, Uzbekistan has revitalised cooperation with its Central Asian neighbours. Improved ties with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan have unlocked regional trade corridors, joint energy projects, and diplomatic initiatives that strengthen Uzbekistan’s position.

This paper provides a comprehensive forecast of Uzbekistan’s economy from 2025 to 2030 and analyses the geopolitical dynamics that will shape that outlook. It is organised into well-defined sections: an overview of macroeconomic projections (GDP growth, inflation, trade balance, FDI, remittances); an examination of Uzbekistan’s relationships with Russia, China, and the U.S.; an analysis of regional relationships in Central Asia; and a discussion of innovative foreign policy and economic diplomacy strategies for balancing global powers while sustaining growth. The report concludes with actionable policy recommendations for Uzbek policymakers and stakeholders to navigate the coming years successfully.

Introduction

Uzbekistan stands at a pivotal moment in its economic and political development. Since the transition of leadership in 2016, the country has embarked on ambitious reforms aimed at liberalising the economy, attracting investment, and reconnecting with neighbours and global partners. These efforts have begun to bear fruit: Uzbekistan’s GDP has grown vigorously (over 6% annually in recent years) and was recalculated to about $100–111 billion in 2024 after incorporating more of the once-shadow economy 5. In 2023, the government adopted a National Development Strategy 2030 with the goal of achieving upper-middle-income status by decade’s end 10. This involves raising GDP per capita to around $5,000 by 2030 (from roughly $2,800 in 2023) 5 10. Achieving these ambitions will require not only sustained economic reforms and sound macroeconomic management, but also adept navigation of a complex geopolitical landscape.

Context and Significance: Uzbekistan’s outlook to 2030 is significant for both domestic and regional stakeholders. Domestically, strong growth is needed to absorb a young and growing population (over 37 million and rising) 13, create jobs, and continue reducing poverty (which fell to 10.9% in 2024 from 13.4% a year prior) 8. Internationally, Uzbekistan is increasingly seen as a pivotal state in Central Asia – the most populous country in the region and one pursuing a proactive foreign policy. Its success in maintaining economic growth and stability has implications for regional development and the balance of influence among great powers in Central Asia. Policymakers thus must forecast economic trends and plan for external opportunities and risks.

Report Structure: This report begins by presenting macroeconomic forecasts (2025–2030),outlining expected trends in GDP growth, inflation, external accounts (trade balance and remittances), and investment flows. Next, it assesses the geopolitical challenges of managing relations with major powers – Russia, China, and the U.S. – highlighting how each relationship impacts Uzbekistan’s economy and autonomy. The following section examines regional dynamics, analyzing Uzbekistan’s partnerships and occasional frictions with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan. Building on these analyses, the paper then proposes novel foreign policy and economic diplomacy strategies that Uzbekistan can employ to maximize its national interest – essentially, how to leverage multilateral relationships and economic tools to maintain a balance among powers and ensure sustainable growth. Finally, the report offers policy recommendations, summarizing key steps for the government and its partners to take in order to realize the optimistic economic scenario while safeguarding Uzbekistan’s sovereignty and stability.

Throughout the paper, the analysis remains accessible and policy-oriented. Where pertinent, data from credible sources such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF), Asian Development Bank (ADB), and others are cited to provide evidence for the forecasts and claims. By combining quantitative forecasts with qualitative geopolitical analysis, this report aims to provide a holistic outlook for Uzbekistan through 2030 – equipping decision-makers with a clear roadmap of challenges and opportunities ahead.

Macroeconomic Forecasts for 2025-2030

Uzbekistan’s macroeconomic outlook for 2025-2030 is broadly positive, characterised by strong growth and gradually moderating inflation, albeit with a persistent but narrowing external deficit. This section details forecasts for key indicators – GDP growth, inflation, trade balance, foreign direct investment (FDI), and remittance flows – and the assumptions behind them. The forecasts incorporate both official targets (such as those from Uzbekistan’s Ministry of Economy and Finance) and independent projections by international financial institutions.

GDP Growth: Sustained Expansion

Uzbekistan is expected to remain one of the fastest-growing economies in Central Asia through 2030. Real GDP growth is projected at 5-6% per year under baseline conditions 10. The World Bank and IMF estimate growth of 5.9% in 2025 8 and around the mid-5% range in the following years, assuming continued structural reforms and strong domestic demand. Similarly, the Asian Development Bank recently revised its forecast upward, projecting growth accelerating above 6% by 2025 14. This robust growth will be driven by several factors:

- Domestic Demand: Private consumption and investment are fuelling expansion. In 2024, for example, private consumption grew 7.5%, and overall investment surged by 27.6% 8. High wage growth, job creation, and remittance-fuelled spending support consumption, while the government’s reform agenda and improving business climate stimulate investment. These trends are expected to continue, keeping growth in the mid-single digits.

- Diversification and Industrialisation: Uzbekistan’s development strategy emphasises industrial modernisation and diversification of output beyond commodities. Growth has been notable in construction, manufacturing, and services. For instance, booming activity in construction, industry, and agriculture contributed to the 6.5% GDP growth in 2024 15. As new industries (e.g. petrochemicals, automotive assembly, textiles, and food processing) expand, they will add to GDP. The opening of new factories – sometimes with foreign partnerships – and improvements in productivity from technology adoption are key assumptions behind the forecasted growth.

- Public and Foreign Investment: The government plans large-scale investments in infrastructure and energy, often with support from development partners. Uzbekistan’s public investment program and FDI projects (discussed further below) will raise the economy’s productive capacity. The National Development Strategy 2030 explicitly targets doubling GDP by 2030; officials now speak of reaching $200 billion GDP by 2030 (up from an initial $160 billion target) 5. While this figure is in nominal terms and aspirational, it reflects an intent to maintain growth above 6% if possible. If realised, per capita GDP would exceed $5,000 (crossing into upper-middle-income status) 5.

- External Environment: The baseline assumes moderate growth in main trading partners and no severe external shocks. Downside risks such as a sharper slowdown in Russia or a drop in global commodity prices could trim Uzbekistan’s growth by reducing export demand or remittances 8. Conversely, upside potentials include higher world prices for Uzbekistan’s key exports (like gold, copper, and natural gas) or faster-than-expected gains from reforms attracting more investment 8. On balance, a growth rate around 5–6% appears achievable and consistent with peers.

In sum, Uzbekistan is on track for steady economic expansion through 2030, consolidating the impressive gains of the past few years. Real GDP is likely to be roughly 1.5 times larger in 2030 than in 2024 (and more than double in nominal USD terms given expected currency and price changes). This momentum will help absorb the roughly 500,000 young Uzbeks entering the labor force each year,though sustaining it will require vigilance against risks and continued pro-growth reforms.

Inflation and Monetary Policy

Controlling inflation has been a central focus of Uzbekistan’s economic management, and forecasts suggest that inflation will gradually decline toward official targets by the late 2020s. After years of double-digit price growth, headline inflation peaked around 10% in 2023–2024 and is projected to ease to 9% in 2025, then further down to about 5% by 2027 8 10. By 2030, inflation is expected to stabilise in the low single digits (around the 5% target or slightly below).

Key factors behind this disinflation trend include:

- Tightening of Monetary Policy: The Central Bank of Uzbekistan has adopted an inflation-targeting framework, using interest rates and other tools to curb price growth 15. Policy rates were raised in response to inflationary pressures (for example, a rate hike to 14% in early 2023) and then adjusted – a 50 bps cut in mid-2024 followed by another hike in early 2025 – to keep inflation on a downward path 10. This proactive stance is expected to continue, with the central bank ready to keep real interest rates positive and credit growth in check to meet the 5% inflation goal.

- Reduction of Subsidies and Fiscal Restraint: The government has been phasing out costly energy and utility subsidies that in the past stoked inflation when adjusted abruptly. In 2024, administered energy tariff hikes caused a temporary inflation uptick to 10.6% 10. However, better targeting of social spending and a planned second round of energy subsidy reforms in mid-2025 will ultimately help reduce fiscal-driven price pressures 10. The commitment to keep budget deficits around 3% of GDP limits demand-pull inflation from the fiscal side 10.

- Stabilising Expectations: As the Central Bank establishes credibility in controlling inflation, public expectations of future inflation should decline. Already by late 2024, inflation had moderated to 9.8% (year-end) 10, and the currency has been relatively stable (depreciating only ~3.7% against the dollar in 2024) 8. International reserves are healthy at about 12 months of import cover 8, bolstering confidence in external stability. These factors help anchor inflation expectations, making price dynamics less volatile.

- External Prices: Uzbekistan, as an importer of certain foodstuffs and consumer goods, benefited from easing global inflation and supply chain normalisation after 2022. Low food inflation in 2024 helped offset other price rises 10. The forecasts assume no major global price shocks (e.g., a commodity price spike) in the latter half of the decade. If such shocks occur, inflation could temporarily overshoot, but the central bank’s framework is expected to bring it back toward target.

By 2030, Uzbekistan aims to have price stability akin to other emerging economies, with inflation possibly in the 3–5% range annually. This is crucial for fostering a predictable business climate and protecting real incomes. The challenge will be balancing disinflation with growth: ensuring that credit remains available for businesses and that relative price adjustments (like utility tariffs) happen smoothly. The outlook is optimistic that Uzbekistan can “have its cake and eat it” – lower inflation alongside high growth, given prudent policies. Indeed, the authorities have explicitly set out to keep inflation at 7% in 2025, 5–6% in 2026, and 5% or below from 2027 onward 5, signalling a strong commitment to price stability.

Trade Balance and External Accounts

Uzbekistan’s external trade will expand significantly through 2030, although imports are expected to continue outpacing exports, resulting in a moderate trade deficit each year. The current account balance (which includes trade in goods and services plus remittances and investment income) is projected to remain in deficit around 5% of GDP in the medium term 8, gradually shrinking as export capacity grows. Key points of the external outlook include:

- Export Growth: Exports are forecast to grow steadily, diversifying in composition. Traditionally, Uzbekistan’s exports were dominated by gold, natural gas, and cotton. By the mid-2020s, non-gold exports were growing rapidly – 16.5% growth in 2024 led by services, food, and chemicals 8 – indicating a broader base. Through 2030, further expansion in manufactured goods, agricultural products, and services (like tourism and IT) is expected. The country’s re-integration into global markets (e.g., anticipated WTO accession by 2025–2026) will open new export opportunities. Official projections also bank on higher exports of gold, services, and manufactured goods helping improve the trade balance 8. By 2030, Uzbekistan could be exporting more finished goods (such as textiles, cars, fertilisers) thanks to industrial investments, as well as electricity to neighbours (leveraging new energy projects).

- Import Needs: Imports will remain sizeable, reflecting Uzbekistan’s ongoing development. Capital goods and industrial inputs are needed for projects in energy, construction, and manufacturing. Consumer imports also rise with income. However, import growth is expected to be modest relative to exports, especially as some domestic production replaces imports (e.g., domestic car manufacturing reducing vehicle imports 8). In 2024, import growth was only 2.3%, partly due to increased local production of chemicals and machinery 8. This trend of import substitution in select sectors (supported by foreign investments in local production) will help contain the trade deficit.

- Commodity Prices and Terms of Trade: Uzbekistan’s export earnings are sensitive to global commodity prices, particularly gold (which still comprised a significant share of exports) and increasingly copper and gas. The outlook assumes relatively firm commodity prices. High gold prices in 2024 boosted export revenues and reserves 8. If gold and copper prices remain high or rise, Uzbekistan could see a windfall, narrowing the trade gap 8. Conversely, a slump in commodity markets is a downside risk. Diversification into non-commodity exports is thus critical to resilience.

- Current Account and Financing: The current account deficit (CAD), which was about 5.0% of GDP in 2024 (down from 7.6% in 2023) 8, is expected to hover around 4–5% of GDP through the late 2020s. Remittance inflows (discussed below) significantly offset the trade deficit by providing foreign currency. With continued reform, FDI and external borrowing comfortably finance the CAD. In fact, the external deficit is by design: Uzbekistan is importing capital to invest in future growth. International financial institutions like the World Bank have assessed that keeping the CAD at ~5% of GDP is sustainable under Uzbekistan’s reform scenario 8. Public external debt was about 35% of GDP in 2024 10 and is expected to decline below 33% by 2027 with fiscal consolidation 8, indicating manageable external obligations.

Overall, Uzbekistan’s external position from 2025–2030 should be stable. Exports will rise but likely not fast enough to eliminate the trade deficit, given robust import demand from growth. The country’s current account deficit, around $7–8 billion per year in the mid-2020s 10, will be financed chiefly by foreign investment and loans, without drawing down international reserves unduly. A continued build-up of currency reserves (already over $40 billion 8, bolstered by gold) will provide a cushion. Policy measures like currency flexibility (some floats with managed interventions) and progress on trade facilitation (modernising customs, transport corridors) also support the external outlook. Importantly, the government’s aim is not to seek a near-term trade surplus, but to ensure deficits remain within safe limits and are used to finance productive investment – a strategy for long-term growth.

Foreign Direct Investment: Rising Inflows

Uzbekistan has become an increasingly attractive destination for foreign direct investment (FDI), a trend that is forecast to continue and accelerate through 2030. Annual FDI inflows have grown from negligible levels a decade ago to several billion dollars in recent years, as the government improves the business environment and opens key sectors to foreign capital. Between 2025 and 2030, FDI is expected to play a central role in financing growth, bringing in technology and creating jobs.

Recent Surge: In 2024, FDI jumped markedly – it accounted for 30.5% of total investment in the economy 8. Major investments have flowed into energy (renewable and oil/gas), mining, manufacturing, and infrastructure. For example, international firms are developing renewable energy projects like solar and wind farms, and building new mining ventures for minerals. During just the first quarter of 2025, Uzbekistan reportedly attracted $8.7 billion in foreign investment, up 20% year-on-year 16, indicating accelerating momentum. While some of this may include loans, it underscores robust foreign interest.

Top Investors: The landscape of foreign investors is diversifying, but China has emerged as the leading source of FDI. In 2024, China accounted for about 28% of all foreign investment and loans in Uzbekistan – the largest share, ahead of Russia (~13%) and othersen.people.cn. The number of Chinese companies operating in Uzbekistan has surged to 3,467 in 2025 (from 2,432 a year earlier), surpassing Russian-affiliated firms 7. Chinese investments span construction, consumer goods, agriculture, and especially green energy and mining 15. Other important investors include Russia (particularly in oil/gas and telecom), Turkey (textiles, tourism), South Korea and Japan (automotive, petrochemical), and increasingly Middle Eastern and European companies. Uzbekistan’s planned accession to the WTO and possible free trade arrangements could further encourage Western investors.

Policy Reforms and Incentives: The government has enacted numerous reforms to attract FDI: simplifying regulations, offering tax incentives, creating special economic zones, and guaranteeing the repatriation of profits. It has maintained stable tax rates (VAT, corporate income tax, etc., kept unchanged for 2025) to provide certainty to businesses 5. High-level visits and agreements – such as President Mirziyoyev’s 2024 visit to China which upgraded ties to an “all-weather” strategic partnership 7 – have unlocked investment pledges. Uzbekistan plans to attract $43 billion of investment in 2025 alone (a figure that likely includes both FDI and domestic investment)en.people.cn, reflecting very ambitious targets. While that single-year figure is high, over the second half of the decade a cumulative tens of billions in FDI is plausible if large projects materialise.

Sectoral Focus: Priority sectors for FDI include:

- Energy: Large projects in solar and wind power (e.g., a 2 GW wind farm by Masdar of UAE) and upgrades to oil & gas infrastructure.

- Manufacturing: Auto assembly plants (with partners from China or Europe), chemical and fertilizer plants, and construction materials are being developed with foreign capital.

- Mining: Gold, copper, uranium, and rare metals mining projects have attracted companies from Russia, China, and the West, given Uzbekistan’s rich mineral endowment.

- Textiles and Agriculture Processing: Investments from South Korea, Turkey, and others in textile factories, and from UAE/Saudi in food processing, add value to Uzbekistan’s cotton and agricultural outputs.

- Infrastructure and Logistics: Foreign firms (often via public-private partnerships) are involved in building new highways, railways, and logistics centres that will bolster Uzbekistan’s role as a transit hub.

The impact of rising FDI is transformative: besides funding the current account gap, it brings know-how and improves productivity. By 2030, FDI will help Uzbekistan industrialise further and integrate into global value chains. Policymakers aim to ensure these investments also create local jobs and that partnerships benefit domestic firms (e.g., through joint ventures). The positive FDI outlook does depend on Uzbekistan maintaining political stability and rule of law, as well as managing public concerns about foreign influence (for instance, ensuring transparency to allay fears of “selling off” assets to foreigners). So far, the government has balanced openness with nationalism by emphasising that foreign investments serve Uzbekistan’s development “quantitatively and qualitatively” 5. If continued, Uzbekistan could emerge as a leading FDI destination in Eurasia by 2030.

Remittance Flows: Lifeline and Growth Factor

Remittances from Uzbek citizens working abroad – predominantly in Russia – are a crucial component of Uzbekistan’s economy and will remain so through 2030, though efforts are underway to diversify migration destinations and reduce vulnerability. Remittance inflows have surged in recent years to record levels, providing hard currency and boosting domestic consumption.

Current Trends: In 2024, Uzbekistan received about $14.8 billion in cross-border remittances, a remarkable 30% increase from the prior year 2. To put this in perspective, this amount is over 13% of Uzbekistan’s GDP – making remittances one of the largest sources of external finance. About 77% of these remittances came from Russia 2. Despite economic uncertainties in Russia, demand for Uzbek labor remained high, and a strong ruble (for part of the period) translated into higher dollar transfers. Interestingly, the number of Uzbeks working abroad officially fell to 1.14 million in 2024 (about 1 million in Russia) 2 ,yet total sent home rose – implying higher average earnings per migrant, possibly due to shifts into higher-paying jobs 2.

Forecast to 2030: The Central Bank of Uzbekistan projects remittances could reach $20 billion by 2027 under a baseline scenario 3, with growth then continuing at roughly 10% per year. By 2030, annual remittances might approach or exceed $25 billion, barring major disruptions. This forecast assumes:

- Steady economic activity in host countries (Russia and others) that require migrant labor.

- A gradual increase in the share of Uzbeks working in higher-income countries (South Korea, the Middle East, EU, etc.) which would boost overall remittance volumes 3.

- A diversification of destinations: indeed, Uzbekistan is negotiating labor export agreements beyond Russia. As more Uzbeks go to countries with stronger currencies and higher wages, the dependence on the Russian ruble will decline 3. This reduces risks; for example, a weakening of the ruble is identified as a key risk to remittance inflows 3. If more earnings are in dollars/euros, that risk is mitigated.

Economic Impact: Remittances will continue to support domestic consumption and investment. Money from abroad often goes into housing construction, small businesses, and household spending on education and goods. The rise in remittances contributed to Uzbekistan’s current account stability – essentially offsetting much of the trade deficit 8. In 2024, a nearly 20% jump in net remittances helped narrow the current account gap 8. This pattern should persist. However, relying too heavily on external labor income has downsides: it indicates limited domestic job absorption, and sudden changes (e.g., geopolitical events in Russia) could disrupt incomes for many families.

Policy Response: Uzbekistan’s policymakers view remittances as both a boon and a vulnerability. The strategy includes:

- Creating better jobs at home so that fewer citizens need to seek work abroad in the long run. Progress on this front (if industry and services expand) may slow the growth of migration by 2030.

- Skilling workers so that those who do go abroad earn more and send more. There are training programs for migrants now, including language and vocational training for jobs in Korea, Japan, and Europe.

- Financial inclusion: Encouraging remittance recipients to use formal banking channels and perhaps invest in financial products can multiply the development impact. The formalization of transfers (shifting from informal cash carriers to bank transfers) has already improved transparency of data.

In summary, remittances will remain a pillar of Uzbekistan’s economy through 2030, supplying hard currency equivalent to roughly 8–10% of GDP each year and sustaining many households. While the goal is to eventually reduce reliance on exporting labor, for this decade these flows are critical. By planning for their effective use and by gradually shifting migrants to more diverse and higher-paying markets, Uzbekistan can turn remittances into a long-term asset while guarding against external shocks.

Balancing Major Powers: Geopolitical Challenges

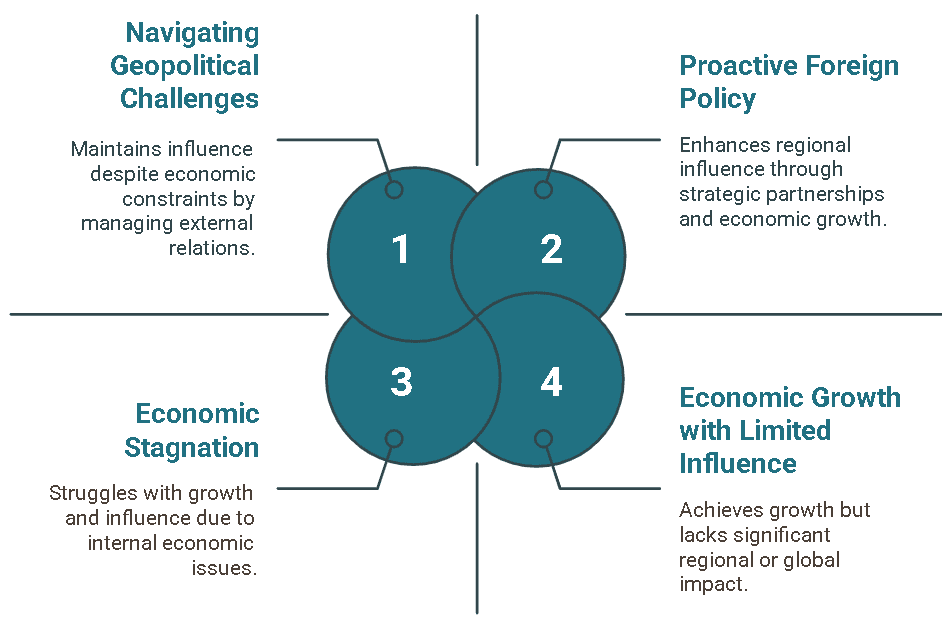

Geopolitically, Uzbekistan finds itself in a strategic position, courted by major powers yet keen on preserving its independence and sovereign decision-making. The era through 2030 will test Tashkent’s ability to manage its relationships with Russia, China, and the United States in a way that safeguards national interests and stability. Each of these powers has distinct interests in Uzbekistan and Central Asia, and Uzbekistan in turn has specific stakes in each relationship:

- Russia: the traditional hegemon in Central Asia, bound to Uzbekistan by historical, economic, and security ties.

- China: an ascending economic force in the region, now Uzbekistan’s largest trade and investment partner, with increasing strategic clout.

- United States: a distant but influential player seeking to support Central Asian sovereignty and regional connectivity as part of its broader great-power competition with Russia and China.

Uzbekistan’s foreign policy under President Mirziyoyev has explicitly been one of “multivector diplomacy,” meaning not aligning exclusively with any one power or bloc 17. Tashkent’s aim is to maintain good relations with all – reaping economic benefits from each while avoiding entanglement in their rivalries. This section examines each bilateral relationship and the challenge of balancing them.

Russia: Navigating a Historical Partnership in Transition

Russia and Uzbekistan share deep ties dating back to the Russian Empire and Soviet Union. Even after Uzbekistan’s independence in 1991, Russia remained a dominant partner. Today, the relationship is still vital but more pragmatic and less asymmetrical than in the past, especially as Russia grapples with its own economic and geopolitical strains.

Economic and Social Links: Russia is a top destination for Uzbek migrant workers (about 1 million Uzbeks were working in Russia in 2024) and thus the source of around three-quarters of Uzbekistan’s remittances 2. It is also a major trading partner – in 2024, bilateral trade was around $11.6 billion, making Russia the second-largest trade partner after China 18. Uzbekistan exports to Russia include agricultural produce, textiles, and metals; imports include machinery, vehicles, and oil products. Furthermore, Russian companies have stakes in Uzbekistan’s energy sector and telecommunications. Culturally, the Russian language remains widely used in Uzbekistan, and educational ties (e.g., branches of Russian universities in Tashkent) are strong.

Security and Political Dimensions: Unlike some neighbours, Uzbekistan is not a member of the Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) or the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) – a reflection of its independent stance. However, it cooperates closely with Moscow on security concerns like border control and counter terrorism. Russia views Central Asia as its strategic backyard and has military bases in neighbouring Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan 4. Tashkent has carefully balanced engaging in security exercises with powers: for instance, it participated in a 2022 regional military exercise with the U.S. and others 4, but avoids steps that Moscow would see as threatening. Uzbek leaders consistently affirm they will not allow their territory to be used against the interests of neighbours, including Russia.

Ukraine War Impact: Russia’s war in Ukraine (since 2022) has reverberated in Central Asia. Uzbekistan, like others in the region, maintained a neutral stance – it did not endorse Russia’s aggression but also refrained from joining sanctions. The conflict indirectly benefited Uzbekistan economically in some ways (e.g., some Russian companies relocated operations to Uzbekistan to evade sanctions; increased Russian demand for Uzbek goods and labor to replace Western imports). But it also raised concerns in Tashkent about over reliance on a sanctioned economy. Notably, Uzbek officials have been vocal about protecting their “independence, sovereignty, and territorial integrity” in discussions with all partners 4, implicitly reassuring that Uzbekistan will not become Russia’s pawn. Analysts note that Russia is currently too preoccupied in Ukraine to exert the same level of attention in Central Asia, and indeed Moscow’s traditional influence is somewhat diminished as it diverts resources and loses some soft power clout 4.

Balancing Act with Russia: Uzbekistan’s strategy toward Russia through 2030 can be summarised as “friendly distance.” It seeks to maintain cordial ties, robust economic exchange, and security dialogue, but without entering formal alliances that limit its freedom. For example, Uzbekistan has opted for observer status in the EAEU rather than full membership, calculating that it can access some trade benefits without ceding economic sovereignty. Tashkent also acts as a regional interlocutor that Russia respects – it has mediated intra-Central Asia issues (like between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan) which indirectly helps Russia by preserving stability. Importantly, Uzbekistan is careful not to host any foreign military bases (a principle in its foreign policy) so as not to upset the regional military balance.

By 2030, it is likely Uzbekistan-Russia relations will remain close but evolved: trade may grow moderately (especially if Russia recovers economically), but China will have clearly surpassed Russia in economic influence in Uzbekistan. Remittances from Russia might plateau or fall if Uzbeks shift to other job markets. Politically, Uzbekistan will continue to reassure Russia of partnership – for instance, regular high-level visits and cultural exchanges – while charting its own course. The challenge will be if Russia, feeling strategic pressure, demands more alignment (for example, pressuring Uzbekistan to limit ties with the West or China). Tashkent will need deft diplomacy to avoid zero-sum choices, emphasising that a stable, sovereign Uzbekistan is in everyone’s interest, including Moscow’s. Given Russia’s likely preoccupation with internal matters and Ukraine, Uzbekistan may have a window to solidify its autonomy without provoking Russian ire, provided it avoids overtly anti-Russian moves.

China: Embracing Economic Opportunity with Caution

In the past decade, China has rapidly moved to the forefront of Uzbekistan’s foreign relationships, especially economically. This trend is expected to intensify through 2030, as China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects and investment in Central Asia grow. Uzbekistan sees China as a critical source of financing, technology, and market access – but is also mindful of the need to manage public wariness about becoming too dependent on Beijing.

Economic Dominance: China is now Uzbekistan’s largest bilateral trade partner and investor. As of 2024, China-Uzbekistan trade reached $13.1 billion, accounting for roughly 19% of Uzbekistan’s total trade turnover 7. This slightly exceeds trade with Russia and is growing year by year. Uzbekistan exports commodities like gold, natural gas, and cotton to China, and increasingly services; it imports a wide array of Chinese goods from machinery to consumer products. On the investment front, Chinese companies are present across various sectors (energy, mining, construction, agriculture). As noted, Chinese firms make up about 22% of all foreign-invested companies in Uzbekistan 7. Major projects include the development of the Zarafshan wind farm, oil and gas field modernisation, and the planned China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan railway, which Beijing is helping fund to create a new trade route. This railway, once completed (perhaps by late 2020s), will shorten transit from China to Middle East and Europe via Uzbekistan, cementing Uzbekistan’s role in BRI connectivity.

Strategic and Diplomatic Ties: In recent years, Tashkent and Beijing have upgraded their relationship to a comprehensive strategic partnership – even termed “all-weather” partnership during Mirziyoyev 2024 visit 7. They have signed dozens of agreements on economic cooperation, infrastructure, security (counter terrorism training, for instance), and cultural exchange. A notable step was the introduction of visa-free travel between Uzbekistan and China in 2024 19 7, which will encourage tourism and business visits. Unlike Russia or the U.S., China keeps a low profile politically; it does not interfere in Uzbekistan’s internal affairs publicly, which Uzbek officials appreciate. However, military ties are limited – China has sold some military equipment (e.g., air defence systems, reportedly even discussions on fighter jets) 20, but there are no Chinese bases in Central Asia (just a small outpost in Tajikistan’s Pamirs).

Economic Dependence vs. Sovereignty: The key challenge with China is balancing the enormous economic benefits against concerns of over dependence. Among some Uzbeks, there is apprehension about China’s influence – a rise in Sinophobia has been observed on social media, fuelled by fears of land or resource “sales” to Chinese entities 7. Viral rumours about Chinese companies buying land or infrastructure caused public outcry, reflecting worries about economic sovereignty 7 . The government has tried to reassure the public, emphasising that Chinese investments are crucial for modernisation and that sovereignty is not at risk 7. But underlying concerns persist about debt (borrowing from China), competition for local businesses, and cultural impact 7. Tashkent is aware that if discontent grows, it could strain the partnership. Thus, maintaining transparency in deals, avoiding unsustainable Chinese debt, and ensuring Uzbeks see tangible benefits (jobs, improved services) from Chinese projects are priorities.

Looking Ahead: By 2030, China’s role in Uzbekistan will likely be even larger:

- Trade could double, especially if new transport corridors reduce costs.

- Chinese investment will be integral to Uzbekistan’s industrial and digital development (e.g., Huawei involvement in telecom, Chinese firms in e-commerce and fintech).

- Projects like the China–Central Asia natural gas pipeline (lines bringing Turkmen gas via Uzbekistan to China) may expand, linking the countries in energy.

- Regionally, China is also promoting multilateral engagement (through the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, which Uzbekistan and China co-founded). Uzbekistan will use forums like SCO to ensure its voice is heard and that Chinese-led initiatives align with regional needs.

Uzbekistan will continue to welcome China’s economic partnership but with open eyes. It will seek to diversify even within that relationship – inviting not just state-owned giants but also private and varied Chinese investors, and pairing Chinese capital with other sources (e.g., jointly with Arab or Japanese partners) when possible. Diplomatically, Uzbekistan will leverage China’s interest in stability: Beijing prefers a stable, prosperous Uzbekistan as it secures China’s western periphery and BRI investments. Therefore, Uzbekistan can assert its autonomy without fear of Chinese political coercion, as long as it safeguards Chinese investments. The motto might be “embrace but never surrender” – integrating with China’s economy while maintaining control of strategic assets and policies.

United States: Engagement on Uzbekistan’s Terms

The United States has historically had a more limited role in Uzbekistan’s affairs compared to Russia or China, but it remains an influential global actor that Uzbekistan seeks to engage, especially for support in reforms, investment, and as a balancing force. Conversely, Washington sees Uzbekistan as a key player in its Central Asia strategy for promoting regional independence from great-power domination and supporting security (e.g., over Afghanistan). Between 2025 and 2030, U.S.-Uzbekistan relations are likely to deepen modestly, albeit within the constraints of geography and competing U.S. priorities.

Political and Security Relations: The U.S. and Uzbekistan have what is now termed a “strategic partnership.” High-level dialogues have increased: for example, in late 2023, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Donald Lu visited Tashkent to discuss boosting trade and investment and “open channels of communication”4. The U.S. consistently voices support for Uzbekistan’s independence and territorial integrity 4 – a message welcomed by Tashkent as reassurance against any external coercion. Military-to-military cooperation exists but is carefully calibrated; Uzbekistan has participated in joint exercises with the U.S. and regional partners 4, and the two countries cooperate on counter-narcotics and counter-terrorism (especially regarding Afghanistan). The legacy of strained ties in the mid-2000s (after the Andijan incident, when the U.S. criticised Uzbekistan’s human rights record and Uzbekistan evicted a U.S. air base) has largely given way to a more pragmatic footing. Both sides understand the relationship will never be an alliance, but a functional partnership focused on mutual interests like stability in Central Asia.

Economic and Developmental Ties: The U.S. is not a top trading partner (bilateral trade is relatively small, a few hundred million dollars). However, the U.S. provides valuable assistance and private investment in specific areas. American firms are involved in Uzbekistan’s energy sector (e.g., Exxon in gas), hospitality, and chemicals, but have room to expand. There is interest in Uzbekistan’s critical minerals (like lithium or rare earths) as the U.S. looks to diversify supply chains away from China. U.S. development agencies (USAID, MCC possibly in future) support projects in agriculture, healthcare, and governance reform. The U.S. has also given technical assistance for WTO accession and other economic reforms 8. Policymakers in Washington often highlight economic connectivity projects such as the Trans-Caspian Trade Corridor and the Central Asia-South Asia energy links as ways to integrate Central Asia globally, which aligns with Uzbekistan’s goals.

Democracy and Human Rights: One area the U.S. consistently raises is human rights and governance. Uzbekistan has made notable improvements (e.g., ending forced labor in cotton fields 4, relaxing some censorship, etc.), but concerns remain, and Washington uses both encouragement and pressure to nudge Tashkent on reforms. For Uzbekistan, engaging on these issues is a balancing act; it seeks better rule of law and governance for its own development, but it resists any perception of external diktat. So far, Mirziyoyev’s “New Uzbekistan” narrative of gradual liberalisation has earned cautious support from the U.S., which in turn has toned down public criticism to focus on partnership.

Balancing Perspective: Uzbekistan views the U.S. as a counterweight that can help limit over reliance on Russia or China. Even limited U.S. security engagement forces Moscow and Beijing to compete in offering favourable terms to Tashkent. However, Tashkent is also wary of being seen as aligning too closely with Washington, which could provoke Moscow or Beijing. For instance, Uzbek diplomats often reassure that U.S. activities like the C5+1 (the five Central Asian states plus U.S.) dialogues are not aimed against any third party. Indeed, a recent analysis advised that deepening U.S. military involvement in the region could “raise Moscow’s threat perceptions” needlessly 4. Uzbekistan likely agrees; it prefers U.S. support in non-military forms – economic cooperation, international lending support, diplomatic backing in multilateral fora – rather than any U.S. troops on the ground.

Looking ahead to 2030, U.S.-Uzbekistan relations are expected to focus on:

- Economic Diplomacy: The U.S. might provide more trade access (possibly removing Cold War-era trade restrictions like the Jackson–Vanik Amendment, which still technically covers Uzbekistan and impedes full normal trade relations 4). Lifting these outdated restrictions would be a goodwill gesture to boost trade 4.

- Investment and Energy: Encouraging U.S. companies in sectors like renewable (wind/solar farms), where American technology excels, or joint ventures in textiles/apparel leveraging Uzbekistan’s cotton (now free of forced labor) 4.

- Education and Culture: Expanding English-language education, exchange programs, and American universities’ presence in Uzbekistan would strengthen soft ties and provide Uzbekistan with skilled human capital that can engage globally.

- Regional Initiatives: The U.S. will likely continue the C5+1 platform. It may also support regional infrastructure like the Trans-Afghan railway to Pakistan (the U.S. International Finance Corporation and others have shown interest in such connectivity which reduces Central Asia’s dependence on Russian routes).

In essence, the U.S. offers Uzbekistan an alternative partnership model – one not based on geographic dominance but on shared interest in an open, independent, and prosperous Central Asia. Uzbekistan will take advantage of this as far as it aligns with its interests, all while reassuring Russia and China that its cooperation with Washington is “fruitful but limited” 4 and not aimed against them. The successful balancing of these relationships will underpin Uzbekistan’s foreign policy autonomy and thereby its ability to pursue economic development unencumbered by great power interference.

Regional Dynamics: Neighbourly Relations in Central Asia

One of the hallmarks of Uzbekistan’s foreign policy since 2016 has been a renaissance in regional diplomacy. President Mirziyoyev famously stated that “Central Asia is the main priority of Uzbekistan’s foreign policy,” and his administration moved swiftly to mend fences with neighbours. Stronger relations with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan are both an end in themselves (promoting regional stability and prosperity) and a means for Uzbekistan to reduce dependence on external powers by fostering local cooperation. By 2025, these efforts have shown tangible results – from resolved border disputes to increased regional trade and even joint infrastructure projects. Between 2025 and 2030, Uzbekistan will likely deepen these ties further, recognising that a united Central Asia can better withstand external shocks and influence.

Key themes in Uzbekistan’s regional engagement include economic integration, water-energy sharing, transportation connectivity, and collective security problem-solving. Below is an overview of relations with each neighbouring country:

Kazakhstan: Strategic Partnership with the Regional Powerhouse

Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, the two largest economies in Central Asia, have cultivated a robust partnership. Historically, there was a friendly rivalry and some competition, but in recent years both Nur-Sultan (Astana) and Tashkent see more to gain in collaboration. Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev and President Mirziyoyev meet frequently and have formed a Supreme Interstate Council to oversee cooperation.

- Trade and Investment: Bilateral trade has been rising rapidly, reaching around $5 billion in 2022 and on track to grow further. In early 2025, trade was reported up 14% year-on-year, reflecting this momentum 21. The two countries have set an ambitious goal to boost trade to $10 billion in the coming years. They are opening new trade corridors – up to four new cross-border trade routes are planned to facilitate faster movement of goods 22. Key exports from Uzbekistan to Kazakhstan include agricultural products, textiles, and electricity (seasonally), while Uzbekistan imports petrochemicals, metals, and wheat from Kazakhstan. Investment flows are also increasing; Kazakh firms are investing in Uzbek banking and retail, and vice versa.

- Connectivity: As Central Asia’s only two double-landlocked nations (neither has direct sea access), Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan rely on each other to reach world markets. They have cooperated on transcontinental transport projects like the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (Middle Corridor) that goes from China through Central Asia and the Caucasus to Europe 4. Both are also stakeholders in potential southward routes to Iran and Pakistan. There is discussion of harmonising customs and even a future common Central Asian market concept that these two could drive. The countries have also improved cross-border mobility; citizens can travel visa-free and border procedures are easing.

- Regional Leadership: Together, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan often coordinate positions in regional summits and have a shared interest in a stable neighbourhood. They have jointly engaged with external partners (for instance, both are part of the C5+1 with the U.S., and both have individual partnerships with Turkey and the EU). There is a sense that Astana and Tashkent form the “twin engines” of Central Asian integration – if they agree on something, the smaller neighbours usually follow. For example, they have together supported the idea of regular Central Asian Heads of State Consultative Meetings, reinvigorating a regional forum that convenes all five nations annually 7.

Going forward, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan will likely continue to strengthen their alliance, focusing on industrial cooperation (co-producing goods for export), energy swaps (Kazakh oil for Uzbek gas or Kazakh coal power for Uzbek hydro power, etc.), and possibly coordinated positions on sensitive issues like water management in the region. A stable, cooperative relationship between these two greatly enhances Central Asia’s collective bargaining power with giants like China and Russia.

Kyrgyzstan: From Boundary Disputes to Brotherly Ties

Uzbekistan’s relationship with Kyrgyzstan has seen some of the most dramatic positive changes in recent years. Under prior leadership, the two countries had serious tensions over border demarcation, ethnic minority issues, and water resources. But the Mirziyoyev administration made resolving these a priority, leading to what can be described as a “new era of cooperation” between Tashkent and Bishkek.

- Border Resolution: In late 2022, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan signed a historic border agreement that settled approximately 99% of their long standing border disputes 12. This included land swaps and joint management of water facilities. A particularly thorny issue, the Kempir-Abad (Andijan) Reservoir, located in Kyrgyzstan and crucial for Uzbekistan’s irrigation, was resolved by transferring the reservoir’s ownership to Uzbekistan while compensating Kyrgyzstan with other land 12. The agreement was lauded by both presidents as turning the border into a “border of friendship” with relaxed cross-border travel rules (citizens can cross with just an ID card now) 12. This breakthrough not only removed a source of potential conflict but also built trust.

- Economic and Infrastructure Cooperation: With political trust improving, economic ties have grown. Uzbekistan has invested in Kyrgyzstan’s economy, including plans for an auto assembly plant and a textile factory in Kyrgyzstan inked during state visits 12. These investments serve both to help Kyrgyz development and also secure markets for Uzbek businesses. Trade is on the upswing, and the countries have even discussed aligning customs regulations to facilitate commerce. Crucially, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan agreed in 2023 on a road map to jointly build the Kambarata-1 hydropower plant in Kyrgyzstan 7. Uzbekistan’s participation (likely as a co-financier and eventual buyer of electricity) marks a stark departure from the Karimov era when Tashkent vehemently opposed upstream dams. This three-way project, if completed by the late 2020s, will generate power for the region and exemplify win-win water-energy sharing.

- People-to-People Contact: There is a growing warmth in social relations. Ethnic Uzbek minorities in Kyrgyzstan (and vice versa) feel somewhat more secure with the thaw in relations. Cultural exchanges are increasing. Direct flights and bus routes between cities have multiplied, and visa-free regimes allow tourism and family visits with ease. The narrative has shifted from mistrust to fraternity – officials refer to each other as close neighbours bound by history.

Despite these gains, the relationship is not without challenges. Internal Kyrgyz politics can be volatile, and not everyone in Kyrgyzstan welcomed the border deal (there were protests in Kyrgyzstan claiming too much land was given away) 12. However, both governments appear committed to the path of cooperation, seeing “no other path but deeper cooperation” as one commentator put it 12. Uzbekistan will continue to support Kyrgyzstan’s stability – including possibly economic aid if needed – because a stable Kyrgyzstan ensures no disruption on Uzbekistan’s eastern flank. By 2030, one could envision a quasi-allied relationship: coordinating in regional bodies, jointly developing border economies, and managing shared rivers and roads in a spirit of partnership. This would be a remarkable turnaround solidifying Central Asian unity.

Tajikistan: Reconciliation and Growing Connectivity

Relations between Uzbekistan and Tajikistan have improved markedly since 2016. Under Islam Karimov, Uzbekistan had a frosty relationship with Tajikistan, characterised by border closures, trade barriers, and disputes over Tajikistan’s Rogun dam project on the Vakhsh River (Amu Darya basin). Mirziyoyev reversed this approach, leading to a rapprochement that continues to deepen.

- Diplomatic Thaw: High-level visits resumed after years of hiatus. Borders were reopened – several crossings that had been shuttered were opened to people and trade. In 2018, President Mirziyoyev visited Dushanbe, and agreements on visa-free travel were reached, allowing Uzbeks and Tajiks to visit each other freely for up to 30 days. Direct flights between Tashkent and Dushanbe, halted for about 25 years, resumed. This normalisation has allowed commerce and interpersonal ties (many Uzbeks and Tajiks have intermarriage or kin links) to flourish again.

- Water and Energy Cooperation: The most significant sticking point, the Rogun Dam, has seen a shift in tone. Uzbekistan dropped its vehement objections to Rogun’s construction; indeed, Uzbek companies even supplied some materials and there were discussions of Uzbekistan potentially investing or buying electricity from Rogun once it comes online. While a formal water-sharing agreement is still in progress, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan now coordinate on water releases and energy swaps. For example, Uzbekistan in summer can import surplus Tajik hydropower, and in winter it can export gas-generated electricity to Tajikistan – a mutually beneficial arrangement. The climate of dialogue reduces the risk of water disputes, which is crucial as climate change makes water more precious.

- Trade and Transit: Bilateral trade, though smaller than with Kazakhstan or Kyrgyzstan, has multiplied in the past few years. Uzbekistan exports a range of goods to Tajikistan, from food to manufactured items, and imports aluminum, electricity, and produce from Tajikistan. The two countries have worked on better transport links: roads have been fixed, and there’s talk of reviving Soviet-era railway links that were cut. One project discussed is a direct railway from Uzbekistan into Tajikistan’s Leninsk (connecting to Tajik rail network) which would bypass a cumbersome route through Turkmenistan. Also, Uzbekistan can now more easily access China via Tajikistan or Afghanistan routes if needed, adding flexibility.

- Security and Regional Alignment: Tajikistan faces security issues with Afghanistan (sharing a long border). Uzbekistan and Tajikistan have found common ground in advocating for moderate engagement with Afghanistan’s new rulers to ensure stability and counter terrorism. They also, along with other neighbours, engage in joint military training and intelligence sharing regarding extremist threats in the region (ISIS-K, etc.). The two nations have also collectively participated in Central Asian presidential consultative summits, presenting a united front on common interests like opposing cross-border militancy and drug trafficking.

There are still some underlying tensions – for instance, Tajikistan has its own great-power relationships (it is closer to Russia, hosting a large Russian military base; and has a unique relationship with China in security). But those do not directly conflict with Uzbekistan’s interests at present. By 2030, Uzbekistan-Tajikistan cooperation is expected to grow, especially economically. A vision of reviving a Central Asian common market or energy grid will rely on these two coordinating. Uzbekistan’s support can also help Tajikistan economically (Tajikistan is the poorest neighbour; more open trade and investment from Uzbekistan can aid its growth). Overall, what was once one of Central Asia’s tensest bilateral ties has turned into a positive example of conflict resolution and win-win progress.

Turkmenistan: Building Links with a Traditionally Isolated Neighbour

Turkmenistan, which is often more insular and neutral, has had a steady if somewhat less dynamic relationship with Uzbekistan. The two countries share a long border and the flowing Amu Darya, but Turkmenistan’s self-imposed isolation (due to its policy of “permanent neutrality”) means cooperation is usually limited to specific pragmatic areas. Under Mirziyoyev, Uzbekistan managed to enhance ties with Ashgabat as well.

- Economic and Energy Cooperation: Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan have complementary economies in some ways. Turkmenistan has abundant natural gas and electricity exports, while Uzbekistan has a larger industrial base. They have engaged in energy swaps: Uzbekistan sometimes supplies Turkmenistan with electricity in winter or imports Turkmen electricity in summer, balancing regional supply. There’s collaboration in the gas sector to – the Central Asia–China gas pipeline traverses Uzbekistan carrying Turkmen gas; both countries coordinate on this strategic pipeline’s operation and expansion. Trade between them includes Uzbek exports of machinery, cars, and agricultural goods, and Turkmen exports of petrochemicals and polymers. The volume is modest (around a few hundred million dollars), but growing as transit improves.

- Transport Corridors to the South: A key area of cooperation is establishing transit routes through each other to access third markets. Uzbekistan relies on Turkmenistan to reach Iran and the Caspian Sea. The two built a railway link from Uzbekistan through Turkmenistan to the port of Turkmenbashi on the Caspian (part of the so-called Lapis Lazuli corridor). Uzbekistan also uses Turkmen roads/rail to reach the Iranian rail network, giving access to Iranian ports like Bandar Abbas. Recently, they have discussed increasing freight traffic through these routes as an alternative to routes via Afghanistan or Russia. This serves Uzbekistan’s aim to be less dependent on any single corridor. Turkmenistan benefits from transit fees and being a necessary partner.

- Political Understanding: Politically, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan have a mutual understanding of respecting sovereignty and neutrality. Turkmenistan is not part of many regional initiatives (it even stays aloof from the consultative summits at times or participates cautiously). But Mirziyoyev and Turkmen President Serdar Berdimuhamedov (and his predecessor Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov) have maintained friendly exchanges. They resolved minor border demarcation issues amicably and even agreed to share water resources – e.g., they coordinate usage of the Amu Darya’s flow to some degree and jointly work on mitigating the Aral Sea ecological disaster, which affects both countries. Turkmenistan’s neutrality means it doesn’t align with Russia or China in any military sense, which actually simplifies Uzbekistan’s balancing act – Ashgabat will not pressure Tashkent to join any bloc. In a sense, Turkmenistan’s stance is an extreme form of what Uzbekistan seeks: avoiding entangling alliances.

By 2030, Uzbekistan-Turkmenistan relations will likely remain pragmatic and cordial. We can expect improved transit efficiency (maybe a faster rail link or streamlined customs on the Uzbek-Turkmen border), possibly joint investments in border regions (special economic zones that cater to both sides), and continued energy cooperation. One potential new frontier is Afghanistan: both Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan are gateways to Afghanistan and have engaged with the Taliban authorities to promote infrastructure (like railways and power lines) that go through their territory. If stability in Afghanistan improves, these projects could significantly benefit both countries by 2030, making them partners in regional connectivity. In summary, Turkmenistan may not publicly bandwagon with Uzbekistan on diplomatic initiatives, but quietly their cooperation will be an important piece of Central Asian integration, facilitated by Uzbekistan’s outreach.

Central Asian Solidarity and Regional Initiatives

Beyond bilateral ties, Uzbekistan has championed the idea of Central Asian solidarity. Under its initiative, since 2018 the Central Asian leaders have held annual consultative summits to discuss regional problems and solutions 7. These summits – held in various capitals by rotation – have led to improved multilateral cooperation, including a landmark agreement on friendship and cooperation signed in 2022. Uzbekistan’s role has often been to propose pragmatic steps that all can agree on, such as creating a joint fund for the Aral Sea or coordinating pandemic responses.

Furthermore, Uzbekistan participates in new regional-minilateral formats:

- The C5 (Central Asia 5) alone (without external powers) for internal coordination.

- C5+1 with various partners (US, Russia, China, EU, Japan, Korea, India, etc.), which allow Central Asia to engage collectively with big players rather than individually – a smarter balance. Uzbekistan has been an advocate for presenting “a common Central Asian stance” in dealings with big powers, where feasible, to increase leverage.

In conclusion, Uzbekistan’s regional strategy by 2030 is to solidify Central Asia as a coherent space of cooperation, which provides a buffer against external dominance. With most disputes resolved or on a path to resolution, and with growing economic interdependence among neighbours, Central Asia as a region can experience a period of joint growth. For Uzbekistan, good relations with neighbours are multipliers for its own economy (enlarging markets, easing access to trade routes) and force multipliers for its foreign policy (speaking with a louder collective voice). The policy of “zero problems with neighbours” that Tashkent has effectively pursued sets the groundwork for a more integrated and resilient Central Asia by 2030.

Strategies for Foreign Policy and Economic Diplomacy

To maintain balance among global powers and promote sustainable growth, Uzbekistan will need to implement innovative foreign policy strategies and economic diplomacy techniques. These strategies build upon the multi-vector approach but go further in creatively leveraging Uzbekistan’s unique position. Below are key strategies that Uzbekistan can employ in the second half of this decade:

1. “Multi-Vector Plus” Diplomacy

Uzbekistan should continue its multi-vector diplomacy – engaging all major powers – but in a more proactive “plus” manner. This means not just passively balancing, but actively positioning itself as a mediator and bridge among powers:

- Regional Mediator Role: Tashkent can offer itself as neutral ground for dialogue (for example, hosting talks on Afghanistan involving the U.S., Russia, and China, or economic forums where all powers are invited). By facilitating communication, Uzbekistan gains trust and reduces great-power friction on its soil 4.

- Alliances on Issues, not Blocs: Uzbekistan can partner with different powers on different specific issues. For instance, work with the U.S. and EU on governance and health initiatives, with China on infrastructure, with Russia on security training, with Japan/Korea on technology – thereby distributing partnerships so no single power becomes dominant. This issue-based alignment keeps relationships compartmentalised and interest-driven.

- Commitment to Neutrality: Formally enshrining (even in law) Uzbekistan’s policy of not hosting foreign bases or not joining military alliances will reassure all sides. It emphasises that Uzbekistan’s sovereignty is non-negotiable and its territory will not be a chessboard in others’ conflicts. This stance helps avoid provoking any of the major powers.

2. Economic Diversification Diplomacy

Economically, Uzbekistan needs to diversify both its export markets and sources of investment to avoid overreliance on any single partner (like China for investment or Russia for remittances).

- WTO Accession and Trade Agreements: Joining the World Trade Organisation (a likely milestone by 2025-2026) will lock in market-oriented reforms and give Uzbekistan equal footing in global trade rules. Post-WTO, Uzbekistan can explore trade agreements or preferential schemes with the European Union (building on its current GSP+ status for tariff preferences) and perhaps the UK or other markets. It can also pursue regional trade pacts within Central Asia. Diversified trade will mean Uzbekistan isn’t at the mercy of one big buyer.

- Investment from a Broad Base: Beyond courting China and Russia, Uzbekistan should deepen ties with the EU, Japan, South Korea, Turkey, India, and Gulf Arab states to attract their investments. Already, countries like the UAE and Saudi Arabia are investing in Uzbek energy and tourism; India is interested in pharma and IT; Europe in textiles and green energy. By engaging these investors (through roadshows, incentives, diaspora outreach), Uzbekistan reduces concentration risk. An example of success would be a future where no single country provides more than, say, 25% of Uzbekistan’s FDI – ensuring balance.

- Remittance Source Diversification: The government can negotiate labor migration agreements with countries like South Korea, Japan, Germany (for seasonal work), GCC states, and others. This would formalise and increase opportunities for Uzbeks abroad outside Russia. Already forecasts note that more Uzbeks going to higher-income countries will diversify remittances 3. Uzbekistan could establish vocational training centres that prepare workers for overseas employment (language and skills), tailoring programs to destination country needs. This “export of labor” diplomacy yields Forex and reduces over dependence on the Russian economy’s health.

3. Regional Coalition Building

Strength at home (in the region) translates to strength abroad. Uzbekistan should institutionalize Central Asian cooperation:

- Central Asian Economic Bloc: Push for a formalised economic cooperation framework among the five Central Asian states by 2030 – potentially a Central Asian Investment Bank or a free trade area. This might start small (common standards, easing border procedures) but grow into something akin to a “Central Asia Economic Union” (distinct from the Eurasian Union). If Central Asia presents itself as a single economic space of 75 million people, it’s more attractive and less easily swayed by outsiders.

- Collective Bargaining with Neighbours: Work with neighbours to collectively negotiate with China on BRI projects to ensure fair terms, or with Russia on transit tariffs, etc. A united regional stance can secure better deals (e.g., collectively ensuring rail transit fees remain low, or jointly resisting any one-sided debt deals).

- Joint Infrastructure Projects: Continue to undertake trilateral projects like the Kambarata-1 dam with Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan 7, or the planned Trans-Afghan railway with Turkmenistan. When multiple countries are invested in a project, it is less likely to be monopolised by an external power and more likely to serve regional interests.

4. Sovereign Economic Resilience

Maintaining economic resilience is also a diplomatic strategy – it gives Uzbekistan leverage by reducing vulnerabilities:

- Debt Management: Keep external debt at moderate levels (as planned, below ~35% of GDP) 10 and avoid unsustainable loans from any single source (especially high-interest loans tied to geopolitical influence). Opt for diverse funding: multilateral development banks, Eurobonds (Uzbekistan has issued international bonds successfully), and various bilateral credits.

- Sovereign Wealth Fund or Reserves: By building a strong reserve cushion (already $41 billion and rising 8), Uzbekistan can weather external shocks like commodity downturns or remittance dips. This financial independence is noted by credit rating agencies; achieving investment grade rating by 2030 5 is a target that, once met, will open even more financing options and reduce reliance on any one patron.

- Local Capacity Building: Invest heavily in education, technology, and governance so that Uzbekistan is making most decisions with in-house expertise rather than foreign consultants or donors dictating. A skilled bureaucracy that can negotiate deals on equal footing with Chinese or Western counterparts is an often overlooked but vital part of economic diplomacy.

5. Cultural and Soft Power Initiatives

Uzbekistan can employ soft power to build goodwill and mutual understanding, which lubricates the harder edges of diplomacy:

- Islamic and Cultural Diplomacy: As a country with a rich Islamic heritage (famed cities like Samarkand and Bukhara) and moderate practices, Uzbekistan can be a cultural bridge between the Muslim world and others. Hosting international cultural forums, reviving the Silk Road heritage in tourism (with involvement of China, Middle East, and Europe), and promoting exchanges through organisations like UNESCO enhances its profile.

- Educational Exchanges: Expand programs that send Uzbek students to study in the U.S., Europe, Japan, etc., while also hosting students from neighbouring countries and even Xinjiang, China. Education ties tend to create long-term affinities and business networks.

- Public Diplomacy: Increase transparency and information sharing with the public about foreign policy choices. For example, combat disinformation that can inflame Sinophobia or Russophobia by proactively explaining the benefits and safeguards of foreign partnerships 7. By doing so, Uzbekistan shores up domestic consensus for its multi-vector policy and prevents external powers from exploiting internal divides.

6. Engagement in Multilateral Institutions

Uzbekistan should amplify its voice in international institutions as part of its diplomacy:

- Within the United Nations, continue to champion causes like the Aral Sea and inter connectivity; perhaps seek a non-permanent UN Security Council seat in the future as Kazakhstan did, to highlight Central Asian perspectives.

- In the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), use membership alongside China, Russia, and India to ensure Central Asian concerns (like Afghanistan) remain central, and resist any Sino-Russian duopoly in agenda-setting.

- In global economic forums (World Bank/IMF, etc.), align with coalitions of emerging economies when interests coincide (for instance, on climate funding or special drawing rights allocations).

- Leverage new groupings like the Organisation of Turkic States (Uzbekistan joined this Turkic cooperation bloc) to strengthen ties with Turkey and Azerbaijan, which also helps balance influences and opens new trade routes (e.g., via the Caspian).

Each of these strategies is designed to give Uzbekistan maximum flexibility internationally and to embed the country in a web of positive-sum relationships. The end-goal is that by 2030 Uzbekistan is not seen as belonging to any one sphere of influence, but rather as a confident, autonomous nation that is friends with all – a “neutral” yet connected hub in the heart of Central Asia. This positioning, combined with sustained internal reforms, will promote the ultimate objective: sustainable and inclusive economic growth for the Uzbek people.

Policy Recommendations

In light of the above analysis, a number of policy recommendations emerge for Uzbekistan’s government and its partners. These recommendations are aimed at ensuring that the optimistic economic forecast is realised and that the country successfully navigates the geopolitical tightrope through 2030. They are presented as actionable steps:

- Sustain Prudent Macroeconomic Management: Continue the course of responsible fiscal and monetary policy. Concretely, keep the budget deficit around or below 3% of GDP and public debt on a downward path 8. Coordinate closely between the Ministry of Finance and Central Bank to manage inflation – for example, if energy tariffs rise, consider targeted cash transfers to the vulnerable rather than reintroducing subsidies. Build on the achievement of reducing inflation to single digits, aiming for the 5% target by 2027 5. A stable macroeconomic environment will encourage investment and make Uzbekistan less vulnerable to external shocks.

- Drive Export Competitiveness: To improve the trade balance and fuel growth, Uzbekistan must boost exports aggressively. The government should invest in export-oriented infrastructure (logistics centres, quality certification labs) and negotiate favourable access abroad. Joining the WTO should be expedited as it will anchor export-friendly reforms. Also, expand the range of exportable products – for example, support the agro-processing industry so that instead of just raw cotton or silk, Uzbekistan exports textiles and garments (value-added goods). By 2030, the aim should be an export basket far more diversified than the current gold-and-cotton heavy mix 8, thereby earning a more stable foreign exchange.

- Catalyse Foreign Investment through Reforms: While FDI is rising 8, competition for capital is fierce. Uzbekistan should further improve its business climate: simplify business licensing, strengthen rule of law and contract enforcement, and accelerate privatisation of non-strategic state enterprises to open space for private investors. Special economic zones need to be made truly “special” with one-stop services. Critical is transparency – publish contracts of major deals to avoid corruption and reassure both the public and foreign partners. Consider establishing an Investment Ombudsman office to resolve investor grievances. With these steps, Uzbekistan can hit its target of moving to investment-grade ratings by 2030 5, which will substantially lower the cost of capital and attract institutional investors.

- Institutionalise Central Asian Cooperation: Uzbekistan should take the lead in formalising regional cooperation mechanisms. One recommendation is to create a permanent Secretariat for the Central Asia Summit that can follow up on summit decisions year-round (e.g., coordinating the implementation of agreements on trade, water, cultural exchange). Another idea is a Central Asia Development Bank jointly funded by the five states for regional projects – this could reduce reliance on external funding and ensure regional priorities get financed. Additionally, continuing the practice of trilateral or quadrilateral summits (such as the proposed first ever trilateral summit of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan 7) can tackle specific cluster issues (like water/energy among those three). The sum effect of these efforts is a more united region that can present common positions to big partners like China and the U.S., exactly as Uzbekistan has advocated.

- Balance Great Power Relations – Avoid Exclusivity: Policymakers should operationalize a simple rule: no exclusive basing rights, no one-country economic zones, and no long-term pacts that preclude other partnerships. For example, if China is involved in a big project (railway, industrial park), also bring in a European or Korean partner if possible for balance. If pressured by Russia to join a bloc or exclude Western influence, politely demur and emphasise neutrality. The Quincy Institute analysis warns that heavy U.S. military engagement could raise tensions with Russia 4; conversely, too much security dependence on Russia could worry others. Thus, Uzbekistan should keep security cooperation broad (SCO exercises, some NATO Partnership drills, bilateral training with Turkey, etc.) so no single power thinks Uzbekistan is tilting too far the other way. Regular strategic dialogues with each major power will help air concerns early – for instance, an annual 2+2 meeting (foreign and defence ministers) with Russia, China, and the U.S. separately could institutionalise communication.

- Leverage Multilateral and Second-Tier Partnerships: Don’t overlook the role of other influential partners. Strengthen ties with Turkey (a cultural and economic partner which can provide investment and is itself balancing Russia and China) – Turkey’s engagement via the Organisation of Turkic States can be a platform. Deepen cooperation with Japan and South Korea, which have long-standing Central Asia programs (e.g., the Central Asia + Japan dialogue). These countries can provide advanced technology and capacity building. India is another emerging partner; follow up on the India-Central Asia summit commitments (India is keen on using the Chabahar Port route via Uzbekistan). By 2030, Uzbekistan should have a very diverse portfolio of allies in trade and diplomacy, ensuring it never faces an “either/or” scenario with the great powers.

- Proactive Public Communications and Inclusion: Domestically, ensure that the public understands and supports Uzbekistan’s foreign policy direction. For instance, in managing Chinese investment, increase public transparency – hold community consultations for large projects to address environmental or social concerns, thereby defusing misinformation that leads to Sinophobia 7. Similarly, highlight the contributions of Russian, American, or other partnerships in concrete terms (jobs created, schools built). An informed public is less likely to fall prey to divisive narratives that external actors could exploit. Moreover, involve think tanks, academia, and the business community in foreign policy brainstorming (through conferences and white papers). Some of the best ideas for balancing powers can come from open discussions in society.

- Future-Proof the Economy: Use the relative stability of now to prepare for long-term challenges. Climate change may stress water and agriculture – cooperate regionally on climate adaptation (the EU can support via its Green Central Asia initiative). Digitalize the economy to participate in the global digital revolution, but also guard against cyber espionage from any quarter by developing local cyber security talent. And crucially, keep diversifying energy (solar, wind projects with international partners) to reduce carbon footprint and dependence on external fuel supplies. A sustainable, modern economy will be more resilient to geopolitical leverage (for example, energy self-sufficiency means not worrying about a neighbour’s gas pipeline pressure).

- Mediation in International Issues: Uzbekistan could carve a niche as a peace broker – a somewhat novel role that boosts its international standing. For example, offer to host talks on Afghanistan’s future (Uzbekistan has already convened such conferences), or facilitate dialogues between powers on issues affecting Central Asia, like water sharing or counter-narcotics. By being seen as a contributor to solving global issues, Uzbekistan gains soft power and respect, which in turn dissuades any heavy-handed treatment by larger states.

- Monitor and Adapt: Finally, establish an inter-agency “2030 Strategy Monitoring Unit” that periodically reviews economic indicators and foreign relations, assessing whether the country is on track or if adjustments are needed. If growth is faltering or a certain power’s influence seems to be growing disproportionately, this unit would raise red flags and recommend policy tweaks. Essentially, treat the 2025–2030 strategy as a living plan, responsive to new data and events (e.g., a sudden change in Russia’s political situation or a breakthrough in US-China relations could alter calculations, and Uzbekistan should be ready to adapt).