A paper by: Alham O. Hotaki

He is an AI and machine learning scientist with over 15 years of experience, from leading the World Bank-funded first e-procurement system to building AI solutions at Deutsche Bank and HSBC. He specialises in data science, MLOps, business analytics, generative AI, large language models (LLMs), AI compliance and automation, as well as cloud and data architecture. He helps organisations build smart, scalable AI solutions that drive real-world impact.

Opening Reflection

I still remember the old community clinic in my hometown. The long queue snaked outside in the heat, as anxious parents held crying children, and elderly folks shifted on aching feet. The nurses and clerks were kind but overwhelmed – there were simply too many needs and not enough hands. I used to wonder: why can’t our technology, which sends rockets to space, help these everyday problems? Years later, I walked into a modern telehealth kiosk in a village. A mother gently speaks into a screen in her own language, guided by an AI health assistant. Within minutes, she has a remote consultation for her feverish son. No long travel, no confusing paperwork – just timely care. My eyes welled up as I witnessed this. It feels almost personal: technology meeting real human needs at last. At that moment, I realised AI isn’t about cold robots or sci-fi dreams; it’s about a grandmother getting her pension on time, a farmer finding out his crop insurance status via a chatbot, a teacher using an AI tutor to help a struggling student. It is about hope that the gap between what people need and what governments can deliver might finally be closing. This chapter is a journey through that hope – exploring how AI agents are transforming public service delivery in health, education, and welfare, with all the promise and the remaining imperfections in between. It’s a topic that stirs both excitement and caution in my heart, like watching a new day dawn over a landscape still filled with shadows.

Understanding Public Service Delivery

Public service delivery refers to how governments provide essential services to citizens – healthcare, education, social assistance, and more – which are the building blocks of welfare and quality of life. Traditionally, delivering these services has been a complex undertaking, often mired in bureaucratic layers and hindered by limited resources. In many countries, citizens have faced hierarchical sluggishness in government systems: slow, paper-driven processes, long wait times, and the sense of being lost in a maze of offices and forms. As societies grow and evolve, these traditional models often fall short of rising expectations and needs[1]. People demand faster, more responsive services, yet governments struggle with budget constraints and ever-expanding workloads.

The result of these challenges is familiar to anyone who has waited months for a passport renewal or spent hours at a public hospital: inefficiency, frustration, and sometimes inequity. Rural and marginalized communities often suffer the most – they live furthest from offices, lack the insider know-how to navigate red tape, or face biases that have crept into human decision-making. Public servants, too, can feel overwhelmed by the volume of cases and the procedural rigidity that prevents them from focusing on individual needs. In short, the traditional public service delivery paradigm has been under strain, revealing gaps in efficiency, responsiveness, and inclusion.

This is where emerging technologies, especially AI, enter the scene with a promise of change. Governments worldwide are reconceptualising how they deliver services by adopting digital platforms and AI-driven tools to streamline processes and better reach citizens[2]. The idea is simple: use technology to do what it does best – handle large volumes of routine work quickly and accurately – so that human officials and social workers are freed to do what they do best – engage with complex cases, exercise judgment and empathy, and design better policies. For example, digital e-government portals now offer 24×7 access to many services, letting people apply for documents or benefits from home, without needing to travel or stand in queue[3]. By reducing unnecessary human interventions and automating checks, these systems can cut bureaucratic delays and even reduce opportunities for petty corruption (no more “agents” asking for bribes to expedite a file)[3]. Done right, costs go down and transparency goes up in the process.

Another key aspect of modernising public service is inclusiveness. A digital approach can expand reach to groups previously left out – if they have access to the technology. AI tools can be designed to operate in multiple languages and formats, making services accessible to linguistic minorities or people with disabilities. We see multilingual chatbots and voice assistants allowing, say, a Kiswahili speaker to interact with government services just as easily as an English speaker[4]. Properly deployed, tech can bridge geographic divides too: remote villagers using telemedicine, or students in far-flung areas getting access to online learning. Indeed, digital ID systems (like India’s Aadhaar) have become foundational in some countries, assigning every citizen a unique number that links to a spectrum of services from banking to welfare[5]. With such systems, it becomes easier to target benefits to the right people and ensure no one is invisible.

Yet, adopting digital and AI-driven service delivery is not a magic wand. It comes with its own challenges – data privacy and security need to be safeguarded, and the persistent digital divide means those without internet or devices could be left even further behind[6]. As of the mid-2020s, roughly one-third of the world’s population still has no internet access[7]. Governments have to grapple with this reality, maintaining “offline” service channels even as they digitise, and investing in digital literacy and infrastructure to ensure new systems don’t unintentionally widen inequality. In this paper, we keep these dual perspectives in mind: the opportunities to greatly enhance public services with AI agents, and the vigilance needed to ensure technology truly serves all people in a fair and dignified way.

AI Transformation Journey in Public Service Delivery

From traditional bureaucracy to intelligent, citizen-centric governance

Paper-driven processes, long wait times, and siloed departments. Citizens navigated complex bureaucracy with limited transparency and accessibility.

Online portals, digital ID systems, and e-government platforms emerged. Services moved online but often still required manual processing.

Intelligent agents automate routine tasks, chatbots provide 24/7 support, predictive analytics identify needs proactively. Real examples: eSanjeevani (163M consultations), Babyl Rwanda, Korea’s AI textbooks.

Truly invisible government: Services anticipate citizen needs, multilingual AI agents accessible to all, preventive intervention before crises, integrated cross-sector platforms like UnityAssist.

How AI Agents Transform Public Services

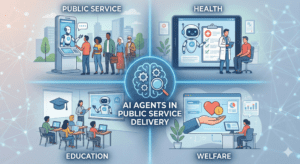

AI agents – which we can think of as software “assistants” or autonomous programs that perceive, decide, and act – are playing a variety of roles in government service delivery today. Their presence is often behind the scenes, embedded in websites, call centres, or data systems, rather than in humanoid robots walking the halls of city hall. But their impact is tangible. Broadly, AI agents in the public sector contribute in roles such as automation of routine tasks, decision support, personalisation of services, and strategic planning. Let’s break these down with examples:

Automation: A major contribution of AI is taking over repetitive, rule-based tasks that consume officials’ time. For instance, consider the flood of applications for a housing allowance or a driving license renewal. Traditionally, clerks might have to sort through each application, verify documents, and cross-check databases – a laborious process prone to backlogs. AI systems can automate much of this: reading and sorting digital documents, checking entries against records for completeness or eligibility, and flagging any discrepancies for human review. In Greece, an AI system now assesses property transaction contracts within 10 minutes, a task that used to take hours of manual scrutiny by staff[8]. By handling the grind of paperwork and initial verification, AI frees up public servants for higher-value activities like resolving complicated cases or actually speaking with citizens.

Decision Support: Not all government tasks can or should be fully automated – many require judgment, context, and ethical considerations. Here, AI serves as an assistant, providing analysis and recommendations while a human makes the final call. For example, Sweden’s public employment service uses an AI decision-support tool to help allocate job-seeker support more efficiently[8]. The AI might analyse various factors – local job market trends, an individual’s work history, skills, even transport availability – and suggest which unemployed individuals might need extra help or which training program could suit someone. The final decision on resource allocation remains with human case officers, but they now have data-driven insights to guide them. In domains like social work or healthcare, AI systems can triage cases (deciding which ones are urgent) or detect patterns (like identifying families at risk of falling through the cracks) and present those insights to human officials. By analysing large volumes of data from diverse sources (text, images, sensor data), AI can flag early signs of service delivery issues or needs that officials might miss[9]. Portugal, for instance, uses satellite image analysis with AI to monitor land use changes, helping urban planners spot unauthorized developments or plan city services proactively[10]. The machine crunches the big data, but humans set the policies on what to do with the findings.

Personalisation and Accessibility: Governments historically have struggled with a one-size-fits-all approach, but AI agents enable more tailored service delivery. An AI can adjust how it interacts with each citizen based on that person’s circumstances and needs, essentially personalising the interface of government. A prominent example is the use of chatbots and virtual assistants on government websites and messaging platforms. These AI chatbots can handle millions of citizen queries in a personalised manner – answering questions, guiding users through forms, even completing transactions – all in plain language. They are “always on” and can scale up to handle spikes in demand (like answering thousands of COVID-related questions simultaneously). Portugal’s government chatbot, for example, is capable of supporting users in 12 different languages and can provide information on over 2,300 public services, ensuring that language is not a barrier for citizens seeking help[11]. Similarly, Greece’s gov.gr portal introduced “mAIgov”, an AI virtual assistant that helps users navigate more than 1,300 digital services; impressively, it supports 25 languages to serve a diverse public and within its first year responded to over 1.6 million queries[12]. Such systems offer intuitive, conversational access to services – a citizen can simply ask, “How do I apply for unemployment benefits?” and get a clear answer or even be walked through the process.

Beyond Q&A, AI enables proactive services that anticipate needs. Rather than waiting for citizens to fill out forms, AI can prompt and deliver services based on life events or predictive analytics. For example, in France a platform called “Services Publics+” uses AI to personalise responses to citizen feedback and even flag systemic pain points in service delivery[13]. This means if many people are struggling with a certain application process, the AI will highlight that issue to administrators for improvement – essentially a feedback loop to increase responsiveness. Going further, consider automatic eligibility checks: AI can cross-reference data to automatically determine if someone qualifies for a benefit and then notify them. Instead of a poor family needing to know about and apply for an energy subsidy, the system could detect their eligibility and proactively grant the assistance – a dignified approach that doesn’t make help so hard to get. This kind of tailored, proactive service is part of the emerging vision of invisible government – doing things for citizens seamlessly in the background.

Planning and Resource Optimisation: AI’s predictive powers are also shaping higher-level public service planning. City governments use predictive analytics to forecast demand and allocate resources accordingly. A classic case is traffic management – cities like Helsinki and Los Angeles feed data from cameras, sensors, and even Google Maps into AI models to predict congestion and adjust traffic light patterns in real time[14]. The same principle of forecasting applies to public healthcare (predicting patient loads or vaccine needs in flu season) and education (predicting enrolment spikes or identifying areas where more teachers will be needed). Singapore has taken this concept to everyday life with its “Moments of Life” app, which is essentially an AI-informed platform that bundles services around key life events[14]. For new parents, for example, the app will send reminders for infant vaccination schedules (healthcare) and prompt the parents when it’s time to enrol the child in school (education). It’s all connected; by anticipating needs, the government can prepare better (assign nurses where an immunization drive is due, or ensure enough school places in a district) and citizens are gently guided rather than left to figure it out alone.

Under the hood, these AI agents rely on big data – drawing together various databases (sometimes historically siloed in different departments) to see the big picture. They can spot trends and anomalies across systems: for instance, detecting an uptick in a particular illness across regions which might signal an outbreak, or noticing that a certain benefit isn’t reaching a particular minority group which could indicate an inclusion gap. By capturing such patterns, AI helps officials shift from reactive firefighting to proactive governance[15]. It’s easier to prevent a crisis than to solve one, and AI tools are strengthening the early warning systems across public services. A concrete example is fraud detection: big data combined with machine learning can reveal suspicious patterns (like multiple welfare claims from the same address) much faster than manual audits, thereby saving public funds and keeping programs credible[15]. Predictive models can also aid in budget planning – forecasting how many people might need unemployment benefits next year given economic trends, thus helping governments allocate funds wisely.

A reflection as we consider these transformations: it is inspiring to see the potential of AI agents to overcome long-standing public sector woes, but it also reminds us that technology is a tool, not a panacea. Every algorithm carries the values and assumptions of its creators; every automated decision can profoundly impact a human life. As we marvel at AI’s efficiency, we must remember efficiency is not the only goal – fairness, transparency, and human dignity are paramount in governance. I find myself amazed by stories of AI catching things a human never could – like predicting a school dropout from subtle signs – yet I also feel a protective instinct that certain decisions, especially those affecting people’s rights and entitlements, must remain guided by human empathy and oversight. In the next sections, we dive into specific domains – health, education, welfare – where AI agents are making waves. Each has its success stories and cautionary tales, and through them we see a common thread: AI can augment the public service mission, but it does not replace the need for good policy, ethical judgment, and the human touch.

AI Agents Impact Dashboard

Transforming public service delivery across Healthcare, Education, and Social Welfare

Cross-Sector Improvements

Global Success Stories

AI Agents in Healthcare

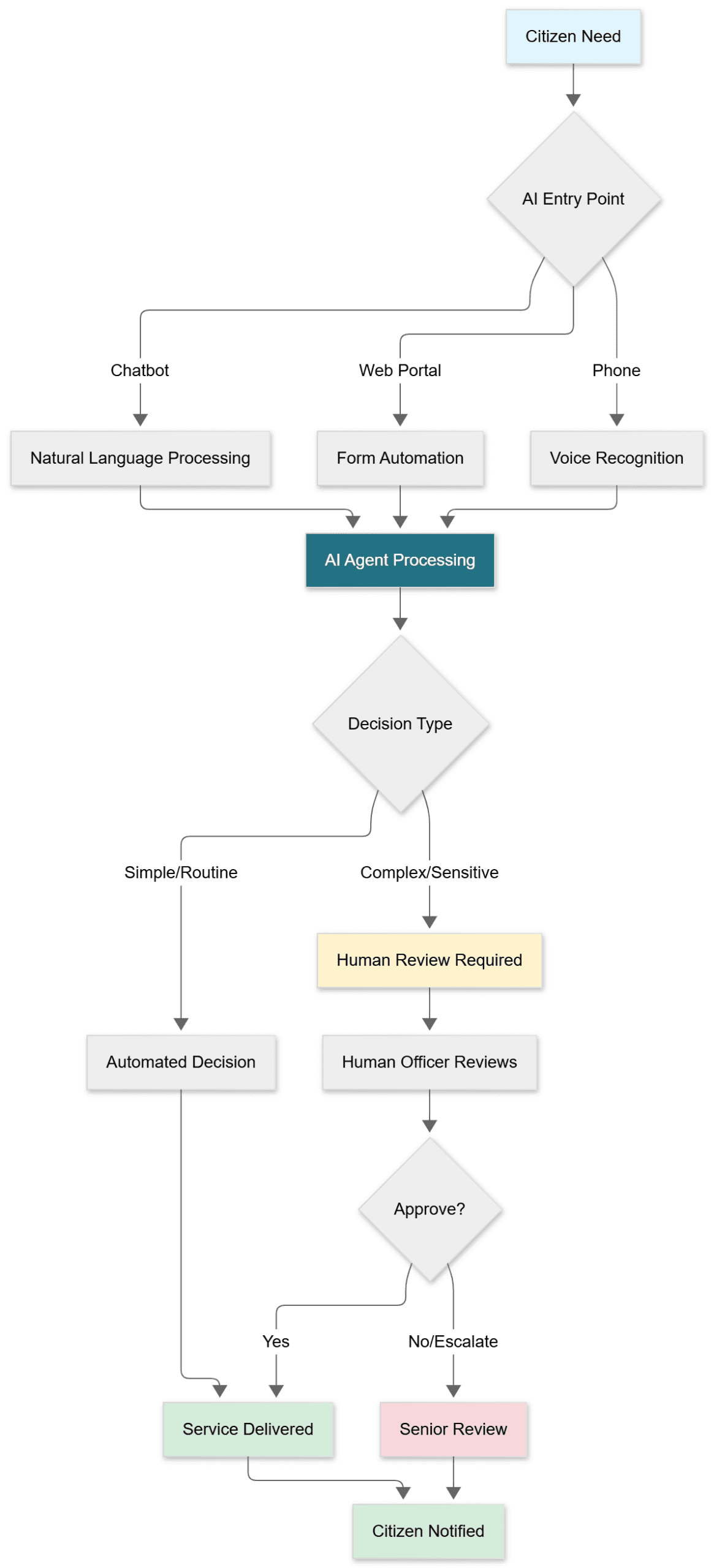

Perhaps nowhere is the impact of AI-driven agents more immediately felt than in healthcare service delivery. Health is deeply personal and urgent – a matter of life, death, and quality of life. AI agents in this sector take on roles from virtual health assistants that interface with patients, to behind-the-scenes algorithms that help doctors make better decisions or public health officials detect outbreaks faster. The goal is to enhance efficiency (treat more people, faster), responsiveness (get the right care at the right time), and inclusion (extend services to underserved communities) – all while upholding the fundamental dignity and care that patients deserve. Let’s explore some key use cases: patient triage and diagnosis, health data tracking, and epidemic prediction and response, highlighting real-world examples such as the World Health Organisation’s initiatives, India’s eSanjeevani telemedicine platform, and innovations in places like Rwanda.

Virtual Triage and Patient Assistance: When you fall sick, the first step is often triage – determining how serious your condition is and what care pathway you need. AI agents have become able helpers in this initial stage. In many countries, symptom-checker apps and chatbots act as a “digital front door” to the health system. You might chat with an AI about your symptoms and it will suggest whether you can safely treat yourself at home, need a teleconsultation, or should rush to the emergency room. This can prevent hospitals from being overwhelmed by minor cases and ensure serious ones aren’t delayed. A striking example comes from Rwanda, a country that has innovated boldly in digital health. Rwanda partnered with the private firm Babylon (locally known as Babyl) to integrate an AI-powered triage tool into its national healthcare system[16][17]. Nurses at call centers use this AI triage assistant when patients call in: the AI systematically collects the patient’s symptoms and medical history through a structured chat and suggests the likely urgency and department for care[17]. Essentially, it’s like giving each nurse a super-smart checklist that adapts to the patient’s answers – a “doctor’s brain in the hands of our nurses,” as the Babyl Rwanda CEO put it[18]. The triage AI has been localized to account for Rwanda’s context – it understands Kinyarwanda (the local language), knows local disease patterns, and aligns with the country’s treatment protocols[19]. The payoff is significant: if a follow-up with a doctor is needed, all the preliminary info is already collected and passed along, saving precious time during the consultation[17]. In a nation of 12 million with only about 1,200 doctors as of a few years ago[20], this efficiency is a lifesaver. AI-driven triage means nurses and community health workers can handle a larger load of initial assessments, referring only the necessary cases up to scarce doctors. It’s a prime example of AI agents augmenting human capacity in an overstretched system.

Another dimension of AI assistance is remote consultations – telemedicine platforms often embed AI to facilitate the interaction. Consider eSanjeevani, India’s national telemedicine service which has scaled to astounding heights. Launched by the Ministry of Health, eSanjeevani provides online medical consultations across the country, and in just four years it facilitated over 163 million consultations across 28 states[21]. While the core of eSanjeevani is connecting patients with human doctors (either directly via a mobile app or through an intermediary health worker at a rural clinic), AI agents are quietly at work in the background. They manage the matchmaking of patient to doctor, ensure medical records and previous consults are available, and maintain the workflow. The success of eSanjeevani challenged many assumptions – it turned out that a low-tech, assisted telemedicine model (patients going to a clinic where a health worker helps them use the service) achieved 93% of the consultations, rather than everyone using their own smartphone[22][23]. This underscores an important lesson in implementing AI in healthcare: context is everything. The technology had to fit the local realities of digital literacy and trust. By embedding within existing community health centers, and essentially turning those health workers into AI-augmented agents of care, India managed to bridge gaps of gender and geography (most eSanjeevani users were women, defying the gender digital divide in phone ownership)[22][24]. AI here acted as the glue binding a network of doctors, health workers, and patients across vast distances. It helped with tasks like recording patient details, scheduling follow-ups, and even translating basic instructions – thus smoothing the telehealth experience.

Decision Support for Clinicians: AI’s role isn’t just at the front door of healthcare – it’s also in the clinic room, supporting doctors and nurses in making diagnoses and treatment decisions. Take the case of clinical decision support systems (CDSS) powered by AI. These are agents that can analyze patient data (symptoms, lab results, medical history) and compare it against vast medical knowledge and datasets to assist a clinician. In practice, a CDSS might alert a doctor if a possible diagnosis is overlooked, suggest optimal medication dosages, or flag high-risk patients in a ward. In many developing countries where expert specialists are scarce, such tools are invaluable. Rwanda, again, provides a pioneering example. In partnership with a local AI company, the government has integrated AI decision support tools for community health workers. One such project involved training a Kinyarwanda-language AI model that can help diagnose diseases in primary care. Early results were astonishing – it improved diagnostic accuracy in pilot tests from a mere 8% (without AI) to 71% when the AI support was used[25]. That leap can literally save lives that would have been lost to misdiagnosis. The AI, essentially, can ingest symptoms and context in the local language and compare against a knowledge base of conditions, narrowing down the likely illnesses. For a health worker in a village who has only basic training, having this AI “assistant” is like having a vastly experienced doctor whispering advice in their ear. It doesn’t replace their judgment – instead it gives them confidence and a safety net to catch mistakes. Rwanda’s success shows that AI solutions can be inclusive when they are localized (language and data trained on local cases) and when they augment the human workforce rather than try to replace it.

Beyond individual patient care, AI agents help health systems make smarter decisions with data tracking and analytics. For example, AI can track outbreaks by monitoring data in real time. The World Health Organisation (WHO) uses a platform called Epidemic Intelligence from Open Sources (EIOS) which leverages AI to scan and filter colossal amounts of information for early signs of public health threats. As of 2020, the EIOS system was gathering over 150,000 news articles per day from around the world about COVID-19 and other potential outbreaks, automatically flagging relevant reports to analysts[26]. No team of humans alone could sift so much daily data. AI’s natural language processing filters out noise and highlights signals (like an unusual cluster of pneumonia in some town’s local news) for epidemiologists to investigate further. Similarly, independent initiatives like EPIWATCH have used AI to comb through open-source data (social media, news, etc.) to issue early warnings for epidemics[27]. These AI agents act as the eyes and ears of global health, potentially buying precious time to respond before an outbreak becomes a full-blown epidemic. We saw during the COVID-19 pandemic how crucial early detection is – some AI systems reportedly flagged the initial outbreak in Wuhan days before official alerts, by noticing a spike in online chatter about unusual pneumonia. In the future, with even more advanced AI, such systems might integrate animal health data, climate data, and travel patterns to predict hotspots for the next disease emergence.

AI is also optimising resource allocation in healthcare – predicting which regions will need more vaccines this season, or which hospitals are likely to face ICU bed shortages next week. By analyzing trends, these agents help smooth out mismatches between demand and supply, making health delivery more resilient. For instance, AI models can forecast the spread of diseases like dengue or influenza using climate and population data, allowing authorities to pre-position medicines and prepare hospitals in high-risk areas. In everyday hospital management, algorithms now predict patient no-show rates or admission surges, so that staffing and bed management can be adjusted proactively.

Real-world examples abound: In India, during the pandemic, an AI tool was deployed in some states to predict which COVID patients would turn severe, so doctors could intervene early. In Tanzania and Ghana, AI-powered drone delivery (an AI agent in a very physical form) has been used to autonomously fly blood and medical supplies to remote clinics, cutting down delivery times from hours to minutes – this blends robotics and AI for a public service outcome. And on the global stage, WHO and UNICEF have been exploring AI for improving vaccine cold chain logistics – ensuring vaccines that require refrigeration are delivered where needed without spoilage, by predicting usage patterns and automatically adjusting supply routes.

A short reflection at this point: the advances in AI for health give me a sense of cautious optimism. I’ve seen how a simple mobile phone with an AI chatbot can empower a villager with health knowledge that was once the guarded domain of doctors. I’ve also seen the relief on a nurse’s face when an algorithm helps double-check her diagnosis, like a colleague watching her back. This is technology with a human heart – when it works, it means a mother doesn’t lose her child to a treatable illness because of late diagnosis, or a city quells an outbreak before it demands a lockdown. However, I also remain aware that healthcare is an area where trust is paramount. An AI could be 90% accurate, but if it misclassifies a critical case as low-risk, the consequences can be tragic. Thus, integrating AI into health must be done with utmost care: rigorous validation, transparency about its suggestions, and always allowing a human clinician the final say and the ability to override the AI. In the success of systems like Babyl in Rwanda or eSanjeevani in India, one common factor stands out – these innovations worked with the health workforce and communities, not around them. The AI agents were introduced gradually, proven in pilot programs, and earned the trust of users. Going forward, the dream is that no one will be left without advice or care at their moment of need because an AI helper will always be available – but achieving that dream must go hand in hand with strengthening the healthcare fundamentals and ethical guardrails. The stethoscope didn’t replace doctors, it enhanced their practice; in the same way, AI should become the new essential tool in the medical bag, one that ultimately amplifies our humanity, not suppresses it.

AI Agents in Education

Education is often described as the great equalizer – the key to personal and societal development. Yet, around the world, educational systems face deep challenges: overcrowded classrooms, overworked teachers, rigid curricula that don’t fit individual students’ needs, and gaps in access or quality especially for rural or disadvantaged communities. AI agents in education aim to tackle some of these issues by offering personalised support to students and automating administrative burdens for teachers. From intelligent tutoring systems and conversational bots that help students 24/7, to AI tools that help school administrators predict and prevent dropouts, these technologies have begun to reshape learning experiences. Importantly, successful integration of AI in education requires sensitivity – it must empower teachers and students, not stifle creativity or human interaction. We will look at examples like AI tutoring bots, automated grading assistants, early warning systems for at-risk students, and how countries like South Korea are rolling out AI in classrooms at a national scale, while organisations like UNESCO guide ethical and effective use through pilot projects and frameworks.

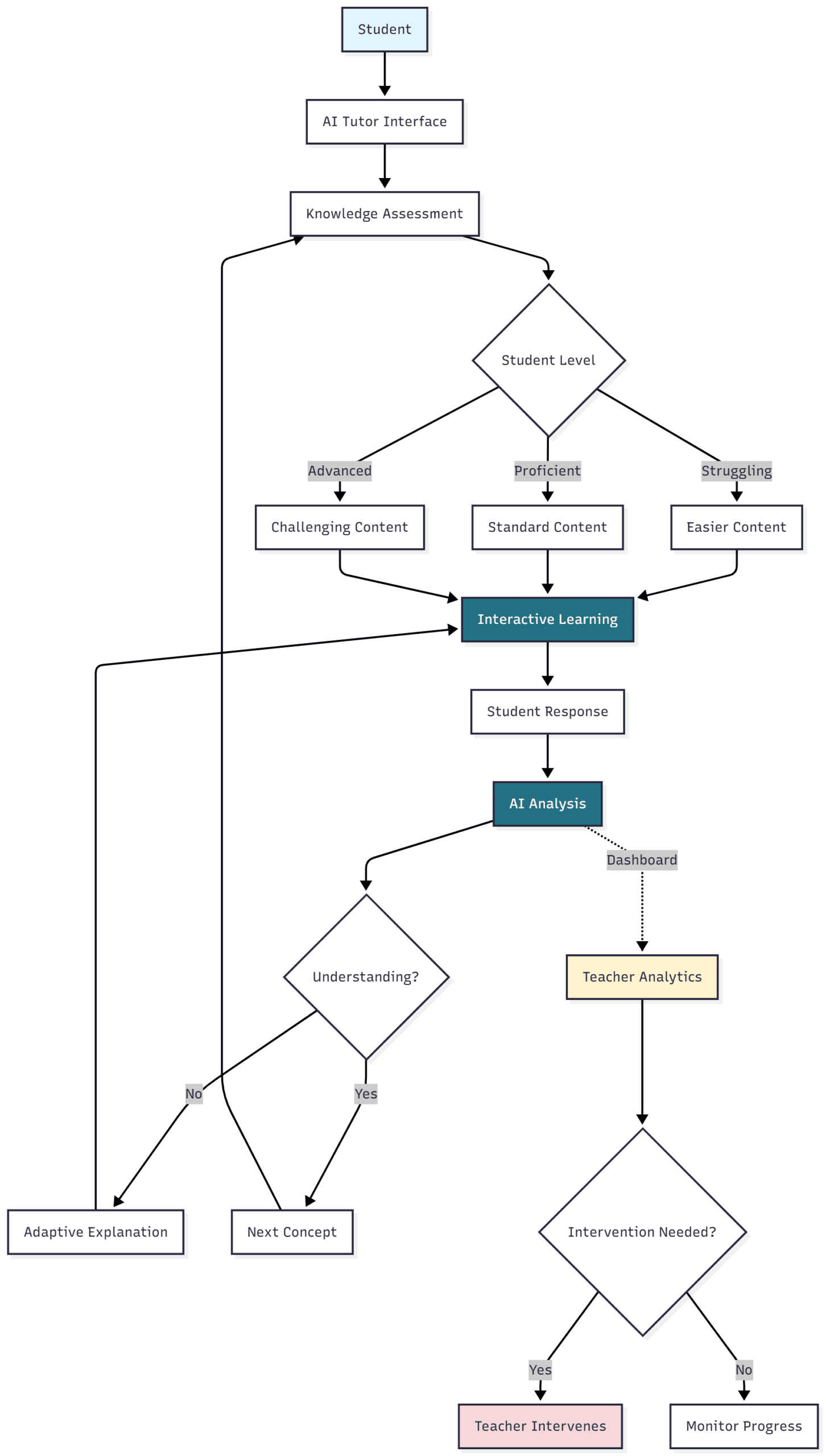

Personalised Learning with AI Tutors: One of the most exciting applications of AI in education is the intelligent tutor – essentially a personal learning assistant for each student. Imagine a chatbot or software agent that a student can ask for help with homework at any time. It explains a tough math problem step-by-step, adapts its teaching style if the student is still confused, and even throws in a relatable analogy drawn from the student’s interests to make the concept stick. This isn’t science fiction; it’s happening in various forms. For example, there are AI-powered learning apps for mathematics that adjust the difficulty of problems in real-time based on the learner’s performance – giving easier problems for concepts they struggle with, and harder ones once they master a skill. This adaptive learning ensures that students neither remain bored because the material is too easy nor do they feel hopeless because it’s too hard. It’s like having a patient private tutor who knows exactly where you need practice.

A notable case is an AI tutoring system used in some pilot projects by UNESCO in partnership with local schools. In one pilot in Rwanda, students used an AI-powered app called Mindspark (originally developed in India) to learn math after school[28]. The AI provided exercises tailored to each student’s level; if a student struggled with fractions, it would spend more time on that, using interactive games and examples relevant to everyday life. Teachers reported that students who used the AI tutor showed remarkable improvement, and perhaps equally important, they were more engaged and confident – the shyer kids would practice with the app and then participate more in class. Such AI tutors also often come with a dashboard for the teacher, highlighting which students might need extra help on what topics, essentially augmenting the teacher’s awareness beyond what she can observe in a crowded classroom.

AI in Classrooms – The South Korea Example: While many AI-in-education deployments are small pilots, South Korea is undertaking one of the most ambitious national rollouts of AI in public education. In 2023, the Korean Ministry of Education unveiled a plan to deeply integrate AI into teaching and learning[29]. A centrepiece of this strategy is the development of AI-enhanced digital textbooks. Starting from 2025, these AI textbooks are being introduced in certain grades and subjects (like English, math, and science) with a plan to cover all grades by 2028[30]. How is an AI textbook different from a regular e-book? For one, it’s interactive and adaptive. It presents content and then, through built-in AI, gauges the student’s understanding via quick quizzes or even by analysing how the student solves problems (where they hesitate, what mistakes they make). It then can adjust the difficulty or provide hints and supplementary material on the spot[31]. For example, if a student is reading a passage and struggles with vocabulary, the AI might provide definitions or easier synonyms; if they breeze through a math exercise, it might skip ahead to a more challenging one. The textbook essentially learns the learner.

From the teacher’s perspective, these AI textbooks are like having an assistant who continually monitors each student’s progress. The textbooks perform real-time data collection on student performance and send analytics to the teacher’s dashboard[31]. A teacher can see which concepts the class as a whole didn’t grasp well (maybe many paused or answered incorrectly on a particular section) and which students are falling behind. This allows for far more targeted intervention – a teacher might group students who need a remedial lesson on concept X, while letting those who excelled move on to enrichment activities. South Korea is pairing this with extensive teacher training, allocating nearly \$0.74 billion over 2024-2026 to train all teachers in using digital and AI tools[32]. The philosophy is clear: AI is there to assist teachers, not replace them. In fact, with AI handling routine tasks like grading or generating practice questions, teachers are expected to have more time for one-on-one mentoring, creative projects, and the social-emotional aspects of teaching[33]. South Korea’s experiment is closely watched globally because it tests AI at scale in a well-funded, well-structured system. Early signs are promising – for instance, in pilot classrooms, teachers reported that students were more engaged and that it actually helped in a country known for competitive stress by personalising the pace of learning to each child, potentially alleviating the race.

The Korean case also underscores the importance of infrastructure and policy support. The government is upgrading school networks and ensuring every student has a device for these AI textbooks[34]. They have issued AI Digital Textbook Guidelines that align with data privacy laws, mandating encryption and prohibiting any misuse of student data[35]. This points to a critical aspect: trust. Students and parents need to trust that an AI is not surveilling children or labeling them forever as “weak” or “strong” students. Korea is tackling this by transparency about what data is collected and ensuring it’s only used to help the student themselves, not for some external ranking[35]. They even have support personnel like digital tutors in classrooms to assist with the tech, ensuring it runs smoothly and helping teachers integrate AI into their lesson plans[36].

Administrative Automation and Early Intervention: Education isn’t just about classroom instruction; a lot of it is administration and student support where AI can also help. Take grading, for example. Grading piles of tests and homework is time-consuming. AI-based grading assistants can already automatically grade multiple-choice exams, and more impressively, assess short essays for things like grammar, coherence, and even creativity to an extent. This doesn’t mean the AI’s score is final – but it can do an initial pass, group essays by score range, and highlight unusual answers for the teacher to review, thereby saving many hours. This gives teachers quicker feedback cycles; students don’t have to wait two weeks to know how they did on an essay, maybe it’s two days now.

Another area is detecting students at risk of dropping out or failing. Schools are beginning to use predictive analytics on student data (attendance records, grades, engagement in activities, etc.) to flag those who show signs of trouble. For instance, if an AI finds that a student’s attendance has been slipping, their grades have declined, and they haven’t logged into the learning portal recently, it might predict a high risk of disengagement. The school counselors or administrators can then intervene – perhaps reaching out to the student or parents to understand what’s wrong (maybe there’s a bullying issue, or problems at home) and provide support early, before the situation escalates to a dropout. These early warning systems are like a safety net woven by AI, catching students who might otherwise fall unnoticed through the cracks. Some U.S. school districts have reported such systems leading to improved graduation rates, as they could personalise support – like offering tutoring or counseling to the specific students flagged.

On a national level, AI can aid curriculum planning. By analyzing job market trends and emerging skill requirements, AI models can suggest updates to school curricula or vocational programs. If data shows, say, a growing need for AI and data science skills (unsurprisingly), a country can decide to introduce basic coding or AI ethics lessons even at the high school level. In fact, Uzbekistan recently proposed at UNESCO the idea of a pilot “School of Artificial Intelligence” to prepare students for the future[37]. This reflects how AI in governance can not only deliver services but inform policy – in this case education policy – by providing evidence-based forecasts.

While AI holds promise, educators and experts caution against an uncritical embrace. There’s a poignant debate: do we want students to be mere operators of AI tools or creative thinkers and creators alongside AI? UNESCO’s 2024 guidance on AI in education emphasizes that we shouldn’t just train kids to be efficient users of AI (e.g., focusing only on how to prompt ChatGPT to get answers) – instead, education should foster a deep understanding of how AI works, its ethical implications, and encourage students to use AI creatively and critically[38]. In other words, the human agency of students and teachers must be preserved. Recent research indicates that if students rely too heavily on AI, their critical thinking can diminish[39]. You can imagine: if an AI helper does all your analysis, you might stop analyzing yourself. So a balance is needed – “human-in-the-loop” design, where AI is a partner, not an infallible oracle. Some schools have started treating AI as a tool students must learn with but also sometimes do without, to ensure they develop core skills. For example, a teacher might allow AI for a project but then have students individually explain the work to ensure they understand it beyond what the AI gave.

A brief reflection on AI in education: I find this area particularly heartening because of its potential to democratize learning. I think of a student in a remote village with few teachers – an AI tutor could open up a world of knowledge for them that their school alone might not provide. I also think of my teacher friends who spend late nights grading papers; if an AI could cut that time in half, imagine the creative lesson planning or one-on-one mentoring they could do instead. But I also feel a sense of protectiveness towards the learning process. Education is not just about information transfer; it’s about socialization, about learning to think and question, about inspiration that often comes from a human mentor. We have to ensure AI doesn’t make education a sterile, individualized screen experience devoid of social learning. The South Korean model interestingly is using AI to enhance human interaction – teachers shift to facilitators of projects and spend more time coaching students[33], which sounds promising. Ultimately, the measure of success will be if students not only perform better on tests, but emerge as more well-rounded, curious, and capable individuals. If an AI can help a child who was struggling to suddenly “get it” and light up with understanding, that’s a wonderful thing. If a teacher can finish her day a bit earlier without compromising quality because AI handled the drudge work, that’s a relief that might keep great teachers in the profession. As we move ahead, we must involve teachers in the design of these AI tools, maintain transparency with parents, and always ask: does this tool respect the student’s potential and privacy? When those boxes are ticked, AI agents in education can truly be a force multiplier for good.

AI Agents in Social Welfare and Assistance

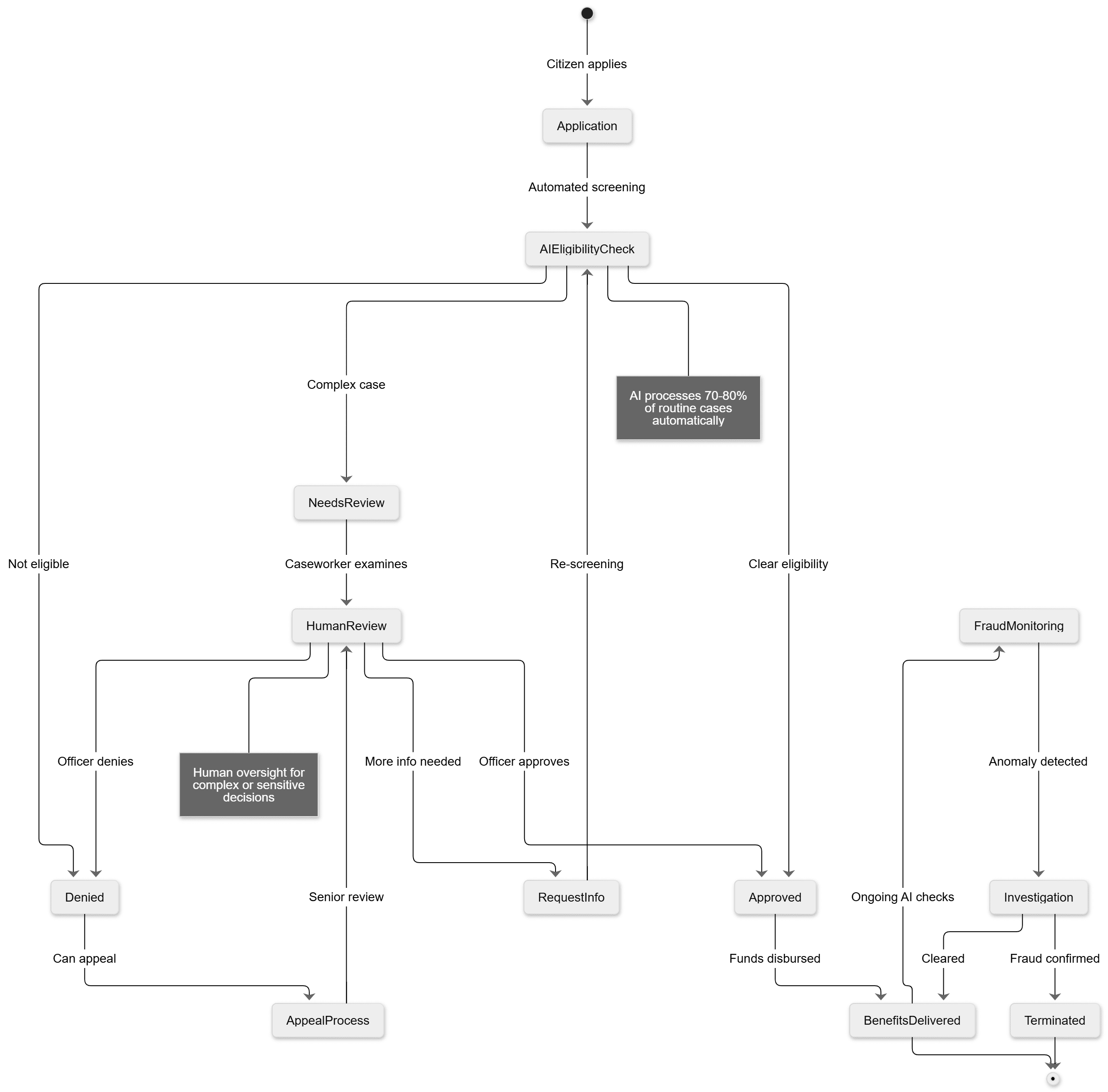

Social welfare programs form the safety net of society – they include benefits and services like unemployment aid, pensions, disability support, food assistance, housing subsidies, and so on. Administering these programs is a massive task, often involving complex rules about who qualifies, verification of documents, continuous monitoring to prevent fraud, and managing huge caseloads of applications and inquiries. AI agents have begun to make inroads in this domain by automating eligibility determination, detecting fraud, and providing direct support to citizens in need. The promise here is quite compelling: faster benefit approvals, fewer errors, more proactive outreach to those who qualify for help, and ensuring that limited resources go to the right people rather than being lost to inefficiency or abuse. However, this is also perhaps the most sensitive area because mistakes or biases in an AI system can directly impact people’s livelihoods and trust in government. We’ll discuss examples from Estonia, Brazil, and Kenya – showcasing both positive outcomes and pitfalls – to understand how AI is transforming social welfare delivery.

Automating Eligibility and Case Processing: Determining if someone is eligible for a welfare benefit can involve dozens of parameters and rules. Traditionally, a caseworker gathers applicant information, checks it against databases (income records, family size, disability status, etc.), and applies legal criteria. This process can be slow – leading to backlogs where applicants wait months for an answer – and sometimes inconsistent, as human judgment can vary. AI systems can encode the complex rules and rapidly cross-check multiple databases, giving near-instant decisions for straightforward cases. The Baltic nation of Estonia provides a shining example of embracing AI for efficient and citizen-friendly welfare services. Estonia has woven AI throughout its digital government, aiming to offer seamless and even proactive services. In fact, the Estonian government’s vision is to create “invisible” e-services that anticipate needs based on life events[40]. In practical terms, when an Estonian loses their job, the system can automatically detect that event (through employment records) and proactively offer unemployment benefits or retraining programs without the person even having to apply[40]. This is implemented via the Unemployment Insurance Fund’s AI-driven system which not only matches job seekers to open jobs (based on their skills and experience) but also predicts who is at risk of long-term unemployment[41]. Those predictions allow the government to channel more counselling and training resources to those individuals early on. The approach is citizen-centric: instead of making a laid-off worker navigate complex bureaucracy during a stressful time, the state – through AI agents – comes to the citizen with solutions, almost like a concerned social worker doing a house call. Furthermore, Estonia’s use of a national digital ID and interoperable data (via its famous X-Road system) means the AI can pull together all relevant information (with consent and legal safeguards) so that people don’t have to submit stacks of documents. The result is faster service delivery that “just works” and is almost unseen. By 2019, Estonia was already launching several seamless services around life events (like the birth of a child or starting a business), linking dozens of government services together via AI so that citizens get a one-stop experience[40]. For example, upon a child’s birth, the system can automatically draft the birth registration, initiate health insurance for the baby, calculate the family’s new benefits, and even put the child on a waitlist for day-care – all the parents might have to do is confirm with one click[40]. This kind of proactive welfare state is a paradigm shift enabled by AI agents working across departmental silos to focus on the person, not the agency boundaries.

Another case: some countries are experimenting with AI chatbots to guide people through benefit applications. Think of an elderly person trying to apply for a pension online; a chatbot can converse in simple language, ask the right questions, fill out the form for them, and even upload necessary certificates if the person takes a photo. It’s like having a virtual clerk available at any hour. Kenya has been advancing in this direction. The Kenyan government’s eCitizen portal, which hosts many services, introduced an AI-powered chatbot (nicknamed the “Huduma [Service] Assistant”) to help citizens navigate services and get information[42][43]. This chatbot, available via web and messaging apps, handles over 60% of initial queries from citizens, giving immediate answers about procedures and eligibility for various services[43]. If someone asks, “How do I apply for the cash transfer program for elderly?” The AI can provide step-by-step guidance or a direct link. By resolving common questions, the AI has cut down calls and visits to government offices significantly – one report noted a 45% reduction in time people spent navigating services on the portal, as the assistant gets them to what they need faster[43]. For citizens, it feels like the government is more responsive; for the government, it reduces workload on human staff who can then focus on more complex cases or on those who truly need personal attention (like someone who’s not digitally literate or has a special situation). Kenya’s embrace of AI also extends to planning social programs. They are looking at using predictive models to identify underserved communities that might need new social centers or to simulate the impact of a policy change on welfare budgets. These are the less visible AI agents that crunch numbers in the background but inform policymakers’ decisions.

Fraud Detection and Integrity: Social welfare programs unfortunately can be targets for fraud – from small-scale cheating (like someone hiding income to qualify for benefits) to large syndicates creating fake beneficiaries. AI offers powerful tools to detect anomalies and dubious patterns that humans might miss. It can cross-verify data across systems to spot inconsistencies (e.g., an applicant claims no income but tax data shows otherwise), and use pattern recognition to flag unusual cases (e.g., multiple benefit applications coming from one single address or IP address). Brazil provides a very instructive example in this arena – both the promise and the pitfalls. The Brazilian Social Security Institute (INSS), responsible for pensions and benefits, introduced AI into its processes in 2018 aiming to cut down a huge backlog of over 2 million pending requests[44]. The AI tool automated the review of many basic claims, like straightforward retirement applications, and indeed helped process thousands of these much faster than before[44]. This was a boon – people didn’t have to wait as long and the agency could reduce its infamous long lines at offices. However, cracks appeared in more complex cases. The AI was also automatically rejecting certain claims that actually needed a nuanced review by a human. For example, a rural worker named Josélia de Brito had her benefit claim denied due to what the AI deemed an inconsistency, but it turns out the situation was common in her region (land owned by one person but farmed by multiple families)[45][46]. People like her, often with little digital literacy and living in remote areas, suddenly saw their lifelines cut off due to “minor errors” or atypical situations the AI wasn’t programmed to handle[44]. This highlights a fundamental challenge: rules-based AI will enforce criteria strictly, which is good for consistency, but life is messy and not every valid case fits the standard mold. Social workers often exercise discretion or bend a rule for compassionate reasons – something a cold algorithm would not do unless explicitly told. Brazilian farm workers’ advocates noticed that the automation was harming vulnerable groups like agricultural laborers with patchy work records, exactly those the system is supposed to protect[47]. The agency defended itself saying the AI just follows the legal criteria and mirrors conventional processes[48]. That is true, but it also showed that if the conventional process had biases or was too rigid, the AI would amplify that.

On the flip side, Brazil has also used AI for genuine fraud detection to good effect in some cases. For instance, by analyzing data patterns, they’ve caught instances where deceased people were still “receiving” benefits or where the same medical certificate was reused by multiple applicants. These are wins – plugging leaks can save funds to channel to those truly in need. But as Brazil’s case showed, the line between catching fraud and denying rightful claims can be thin if the system isn’t carefully calibrated and if there’s no easy way for people to appeal an AI-based decision. Argentina and some other Latin American countries have even used AI (like ChatGPT-based tools) to draft parts of social services decisions or communications, speeding up administrative work[49]. Costa Rica uses an AI system to scan tax data for signs of fraud in digital invoices, indirectly ensuring more revenue for social spending[50]. El Salvador set up an AI lab to develop government service tools, potentially including welfare management improvements[51]. Latin America is clearly a region embracing these efficiencies, but experts urge that transparency and recourse mechanisms keep pace. As an expert from Amnesty International noted, “No government wants to be left behind in the AI race, so it’s being deployed without proper testing, reinforcing systemic issues and bias”[52]. This sobering observation came after studies found welfare algorithms in Europe and elsewhere entrenching biases (we’ll touch on that in the Challenges section).

Citizen Support and Outreach: Another angle is using AI to improve the experience of citizens interacting with welfare agencies. Much like in other sectors, AI chatbots or voice assistants can handle common inquiries: “When will I receive my payment this month?” “How do I update my address for my benefits?” etc. This 24/7 availability is especially helpful for people who might work during office hours and can’t easily visit an office or call a hotline then. For example, in some states in India, conversational AI systems have been piloted to assist people in checking the status of their ration card (food subsidy) or to guide them on getting a disability certificate. These systems often have to handle multiple languages and even dialects, given the diversity of users. The technology of voice recognition has advanced enough that an AI can understand a question asked in a local accent over a basic phone call, and respond with synthesized speech, making it accessible to those who cannot read. This kind of inclusive design is crucial for social welfare, because often those needing help the most are the least likely to be tech-savvy or well-educated. AI agents can bridge that gap by becoming simpler, friendlier interfaces to bureaucracy.

A remarkable idea being explored in some innovative circles is using AI to simulate policy changes and find people who are eligible for benefits but not enrolled. For instance, an AI model can take all the data on citizens and run a scenario: “If we raised the income threshold for child support by 10%, who and where are the new beneficiaries?” Policymakers can use this to understand the impact and cost of expanding programs. More granularly, a welfare department could use AI to scan through population data and identify households that meet criteria for a program but haven’t applied. There are pilot programs where the government then proactively reaches out to those families – via a text or local officer visit – to inform them that help is available. This flips the script from citizens having to know and seek out programs to the state actively searching and ensuring no one is left behind due to lack of information. It’s like the welfare AI becomes a social detective, finding hidden pockets of need.

Now, consider Estonia again for a success story on integrity combined with service. Estonia plans to implement something they call KrattAI, a sort of government-wide virtual assistant that can carry out tasks across agencies[53]. One could envision asking the Estonian e-assistant: “I lost my job, what should I do?” and it would automatically file for unemployment benefits for you, check if you’re eligible for subsidized training, and help you update your health insurance – all in one conversation. Such holistic AI agents could greatly simplify the citizen experience. Importantly, Estonia is also mindful of not making these systems black boxes. Their government CDO has spoken about how crucial it is to maintain public trust – they are phasing AI in carefully and making sure people can always talk to a human or appeal a decision easily[54][40]. The paradigm is that AI handles routine decisions, but humans remain for the complex or contentious ones.

Reflecting on social welfare automation, my feelings are mixed – a blend of optimism and concern. On one hand, I’m heartened by stories like an Estonian single mother who doesn’t have to fight through paperwork to get aid when she has a baby; the system congratulates her and asks where to deposit the support money. That is technology upholding dignity – removing the old stigma and hassle around welfare. On the other hand, I read about the Dutch childcare benefits scandal: an algorithm profiled immigrants as high risk and led to thousands of parents wrongly accused of fraud, plunging them into debt and distress[55][56]. It was so severe it caused a government crisis in the Netherlands. This is a cautionary tale of AI gone wrong, or rather, data-driven policy gone wrong by amplifying biases (in that case, essentially flagging anyone with dual nationality). Similarly in the UK, a misguided algorithm for exam grading had sparked outrage for unfairly downgrading students from certain schools. These examples remind me that when AI agents make decisions about welfare, they are deciding who gets to live with basic security and who doesn’t. There’s a moral weight there that we cannot delegate entirely to machines or to cold data. My hope is that we learn from early missteps: build systems with transparency (so their criteria can be scrutinized), with community input (so they reflect societal values of fairness), and with robust grievance redressal mechanisms (so if a person feels a decision is wrong, they can quickly get a human review and fix). The positive examples show that AI can truly make welfare delivery more humane by cutting delays and proactive outreach. The negative ones show that if we’re not careful, AI can institutionalize discrimination at a scale faster than any individual bureaucrat ever could. As we proceed, striking that balance – efficiency with empathy, automation with accountability – will define whether AI agents in social welfare are remembered as a triumph or a cautionary footnote.

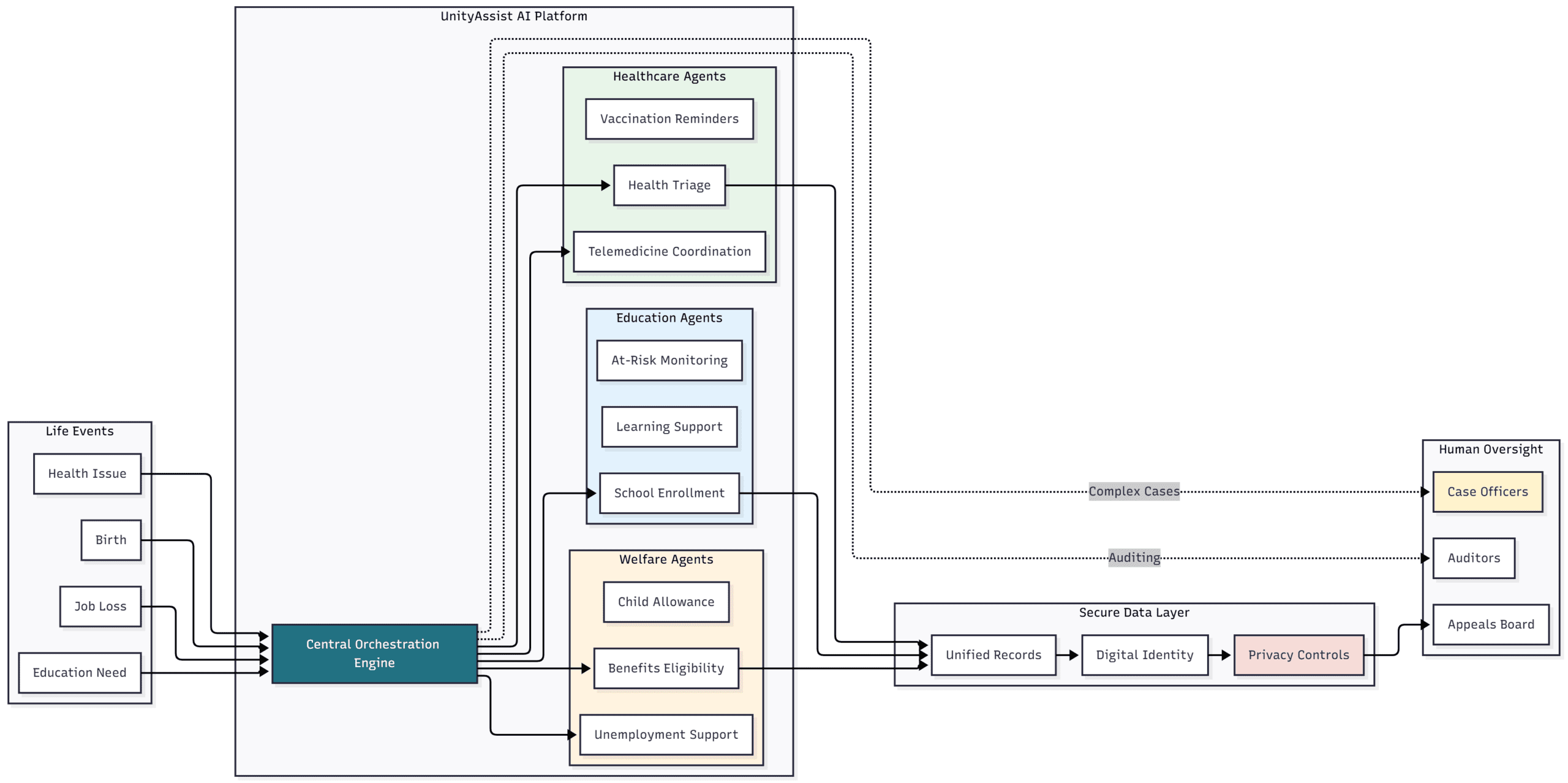

Case Study – Integrating Agents Across Sectors

To really illustrate the power and potential pitfalls of AI agents in public service, let’s imagine a holistic case that ties together health, education, and welfare services into one integrated AI-driven platform. This case study will be a composite – inspired by real initiatives in various countries (like Singapore’s life-event approach, Estonia’s proactive services, and others we’ve touched on). We’ll call this imaginary system UnityAssist – a national AI-enabled platform that serves citizens across multiple needs seamlessly. Through UnityAssist, we’ll walk through a scenario of a citizen interacting with the government from the birth of a child to raising that child, to highlight how AI agents can unify services that traditionally existed in separate silos. We will also examine the benefits of such integration and the risks that come with concentrating so much in one system.

Scenario: Maria and Jose are a young couple in Country X, living in a semi-rural area. Maria just gave birth to their first child, a baby girl named Sofia. In the past, Maria and Jose would have to register Sofia’s birth with the civil registry, apply for a birth certificate (maybe traveling to a city office), separately enrol the baby in the national health system, and perhaps file for any child benefit payments or parental leave – each likely at a different office or website with its own forms. This often meant weeks of running around, and if they missed a step, Sofia might not get all the services she’s entitled to. But now, thanks to UnityAssist, an AI agent handles these tasks proactively.

The moment Sofia is born at the local clinic, the health system’s computer (which is connected to UnityAssist) creates a digital record of a new birth. UnityAssist springs into action: it cross-verifies the birth with the national ID database to record a new citizen, essentially initiating Sofia’s digital identity linked to her parents. Maria receives a friendly message on her phone from the government’s virtual assistant: “Congratulations on your baby girl, Sofia! We’ve registered her birth. Here is a link to download her digital birth certificate. We noticed you might be eligible for the ChildCare Allowance – would you like to proceed to claim it?” Maria, still in the hospital bed, is amazed – with one click she consents, and UnityAssist files the allowance claim automatically, since it already has all needed info (the baby’s birth, the parents’ income from tax records, etc.). The next day, Jose gets another notification: “Your child has been enrolled in the National Health Program. Please pick a pediatrician from this list in your area or tap here for UnityAssist to assign the nearest available pediatric clinic.” They select a clinic, and an initial check-up appointment is scheduled by the AI, complete with a map and date.

Over the next months, UnityAssist continues to be their helper. It sends reminders for Sofia’s vaccination dates, even personalised in their preferred language, with a gentle tone: “Sofia is due for her 6-month vaccinations next week. Would you like to schedule it now?”[14]. Maria can just reply “Yes,” and the AI schedules at their chosen clinic, adjusting around Maria’s own work schedule (which it knows from her calendar, because she allowed that integration). When Sofia is a toddler, UnityAssist informs them about early childhood education programs nearby, and once Sofia turns 4, it proactively notifies the family about preschool enrollment: “Applications for preschool are open. We have pre-filled the form for Sofia based on your info; please review and submit by clicking here.” The form is indeed ready – all Maria has to do is choose from a list of preschools. The AI even ranks them by proximity and user ratings (yes, citizens can rate services and the AI aggregates feedback).

Now, consider that during this time, Jose unfortunately loses his job. The AI agent picks up on this through the social insurance data – it notices contributions stopped coming from Jose’s employer and a separation record was filed. UnityAssist, respecting privacy settings, pings Jose: “We saw you separated from your job – sorry to hear that. Can we help you file for unemployment benefits or look for new job opportunities?” When Jose says yes, the AI already has his employment history and salary details, so it submits the unemployment claim that same day and informs him, “Your first benefit payment of X will arrive in 10 days. Meanwhile, I found 3 job listings in your field within 20 km. Would you like me to email you the details or set up alerts for new postings?” This kind of integrated response softens what otherwise would be a familial crisis. Maria and Jose don’t have to navigate a separate welfare office bureaucracy while worrying about their finances – it’s handled in one place with minimal effort.

Fast forward a few years: Sofia is now in primary school. UnityAssist helps here too. It regularly updates Maria and Jose on Sofia’s school attendance and can even help them with school-related processes. For example, the school district uses an AI system to identify students who might need extra help in reading. UnityAssist notifies Maria that Sofia seems to be struggling with reading fluency compared to peers, and suggests a government-sponsored AI tutoring app for reading that she can use at home, or free enrollment in an after-school reading program. This alert is sensitive – it doesn’t label Sofia as “behind” in a judgmental way; rather it says “Every child learns at their own pace. Here are some resources to support Sofia’s reading development.” The parents accept, and Sofia starts using a fun reading game at home that adapts to her level.

In the background of all this, UnityAssist is not a single monolithic AI, but a coordinated network of specialized AI agents (one focusing on health, one on education, one on welfare, etc.) that communicate with each other through a common platform. This network is governed by strict data privacy and ethics rules. For example, when the education AI flags Sofia’s reading issue, it does not share her personal data with third parties and it only does so because the parents opted into academic support services. All decisions that impact benefits or rights (like approving the unemployment claim or assigning a school) are transparent: UnityAssist provides explanations if asked, like “We approved your ChildCare Allowance because your household income (which is \$Y) falls below the threshold \$Z for a family of your size[44].” If any decision were adverse (say if Jose’s unemployment claim was denied), the system would automatically escalate it for a human review and provide Jose with information on how to appeal, ensuring no one is left confused by a machine’s rejection.

Benefits of Integration: The integrated approach brings huge convenience. Life doesn’t happen in silos – when a baby is born, it triggers health, legal, and welfare needs at once; when someone loses a job, it affects their family’s education plans, health insurance, and income support. UnityAssist’s cross-sector integration means citizens don’t have to figure out which department does what, or fill the same information multiple times for different agencies. It treats the citizen’s life events holistically[40]. This not only saves time and hassle, but also likely increases uptake of benefits and services (many people miss out on programs simply because they didn’t know or couldn’t complete complicated processes). Moreover, it can reduce errors and corruption – there’s less manual processing and discretion at local offices, so fewer chances for mistakes or someone asking for a bribe. The digital trail is clear, and data once entered populates everywhere necessary.

For governments, integrating services via AI can lead to cost savings in the long run. Maintaining one unified system may be cheaper than each ministry having its own IT infrastructure (though initial investment is high). It also enables data-driven policy: anonymized data from UnityAssist can reveal insights, like how certain benefits are often used together or how early childhood program uptake improves school performance later. These feedback loops can inspire new combined initiatives, like maybe linking a nutrition program with early education in policy because the data showed it’s the same vulnerable population needing both.

Risks and Challenges: However, such an integrated system is not without significant risks. First and foremost is privacy and security. UnityAssist holds a treasure trove of personal data – health records, financial info, academic reports, you name it. This makes it a high-value target for cyberattacks. A breach could be disastrous, exposing the sensitive information of millions. Thus, the system must employ state-of-the-art security and constant vigilance. There’s also the concern of “big brother” – some citizens might fear that the government (through AI) is watching every aspect of their lives too closely. Even if the intentions are good (to help them), the feeling of being monitored can erode trust. Transparent governance of UnityAssist is needed, possibly with independent oversight to reassure that data is only used for the intended purposes (no function creeps into surveillance, for example).

Another issue is algorithmic errors or biases being amplified across sectors. If UnityAssist has a flaw in how it assesses something, that error could cascade. For example, suppose the algorithm that predicts school needs mistakenly correlates low income with learning disability (due to biased data). It might over-recommend remedial services to poorer families, perhaps stigmatizing them or misallocating resources. Or if there’s a glitch in identity matching, someone might get accidentally marked deceased (it has happened in real systems) and then all their benefits and services across the board could stop at once. That kind of all-encompassing failure is the nightmare scenario of integration – a single point of failure affecting everything. To mitigate this, the system must be designed with redundancy and fallbacks (and, again, human override teams who can quickly step in and correct things if an alert is raised).

We should also consider digital divide issues. In our scenario, Maria and Jose had phones and could interact with UnityAssist digitally. But what about citizens who don’t have smartphones or who aren’t comfortable with tech (imagine an elderly person living alone)? An integrated system must have multiple access points: perhaps village kiosks with human helpers, voice-based access for those with basic phones (the AI could call them or vice versa), and maintaining a human staffed hotline or office for those who really need it. A fancy AI platform that only the connected and educated can use could worsen inequality, leaving the most vulnerable even further behind. So, an implementation plan for UnityAssist would involve digital literacy campaigns and maybe providing devices or community access points so that everyone can benefit.

Human element: Even with UnityAssist doing the heavy lifting, the human frontline workers are not going away – they are evolving. Social workers, teachers, nurses, etc., would use UnityAssist as a tool to inform their work. Ideally, by automating paperwork, these professionals have more time to directly engage with clients/citizens. In tricky cases, a human touch might be dispatched by the AI; for instance, if UnityAssist detects someone might be in crisis (say, multiple indicators like job loss, health issues, missed appointments), it could flag a human social worker to intervene personally, recognizing that an AI message alone may not suffice for complex, sensitive outreach.

In summary, the integrated case of UnityAssist shows what the future could hold: a citizen-centric government service that is as easy as having a personal assistant who knows you and is looking out for you. It blends healthcare, education, and welfare such that to the citizen, those separations blur away – it’s just “my government helping me in life.” The benefits are enormous in terms of user experience and possibly outcomes (healthier children, more efficient welfare use, etc.). But it comes with heavy responsibility to get it right. Trust in such a system would be hard-earned and easily lost. A single high-profile failure (like a systematic wrongful denial of benefits to a minority group, or a data breach) could make people lose faith and reject the system. Therefore, building UnityAssist would require not just brilliant tech integration, but also strong legal frameworks, ethical guidelines, continuous community feedback, and rigorous testing and auditing. Some nations are taking steps toward this integrated vision in pieces: Singapore’s Moments of Life app is a step in this direction for early childhood, bundling multiple agencies in one app[14]. New Zealand’s SmartStart is another example focusing on services for new parents in one place[57]. These are building blocks for a UnityAssist-like future.

As I reflect on this case, I feel a mix of excitement at the sheer convenience and support such systems can provide, and caution at the power they wield. It’s akin to the excitement of discovering a new all-in-one gadget that can do everything – but you know if it breaks, you lose a lot at once. The key takeaway for me is that integration must go hand in hand with empowerment: citizens should feel more in control of their information and benefits, not less. They should feel the government has become more like a friend and advisor, not an overbearing nanny or snoop. Technologically, the case study is within reach given current advances. Socially and institutionally, it will require careful, democratic governance. Perhaps the best approach is iterative – start by integrating a couple of services, ensure it works and is accepted, then expand. In any event, the integrated AI agent approach indeed represents a frontier for good governance where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Global AI Success Stories in Public Service

Real-world implementations transforming healthcare, education, and social welfare across continents

Transforming Public Services Worldwide

Global Impact Summary

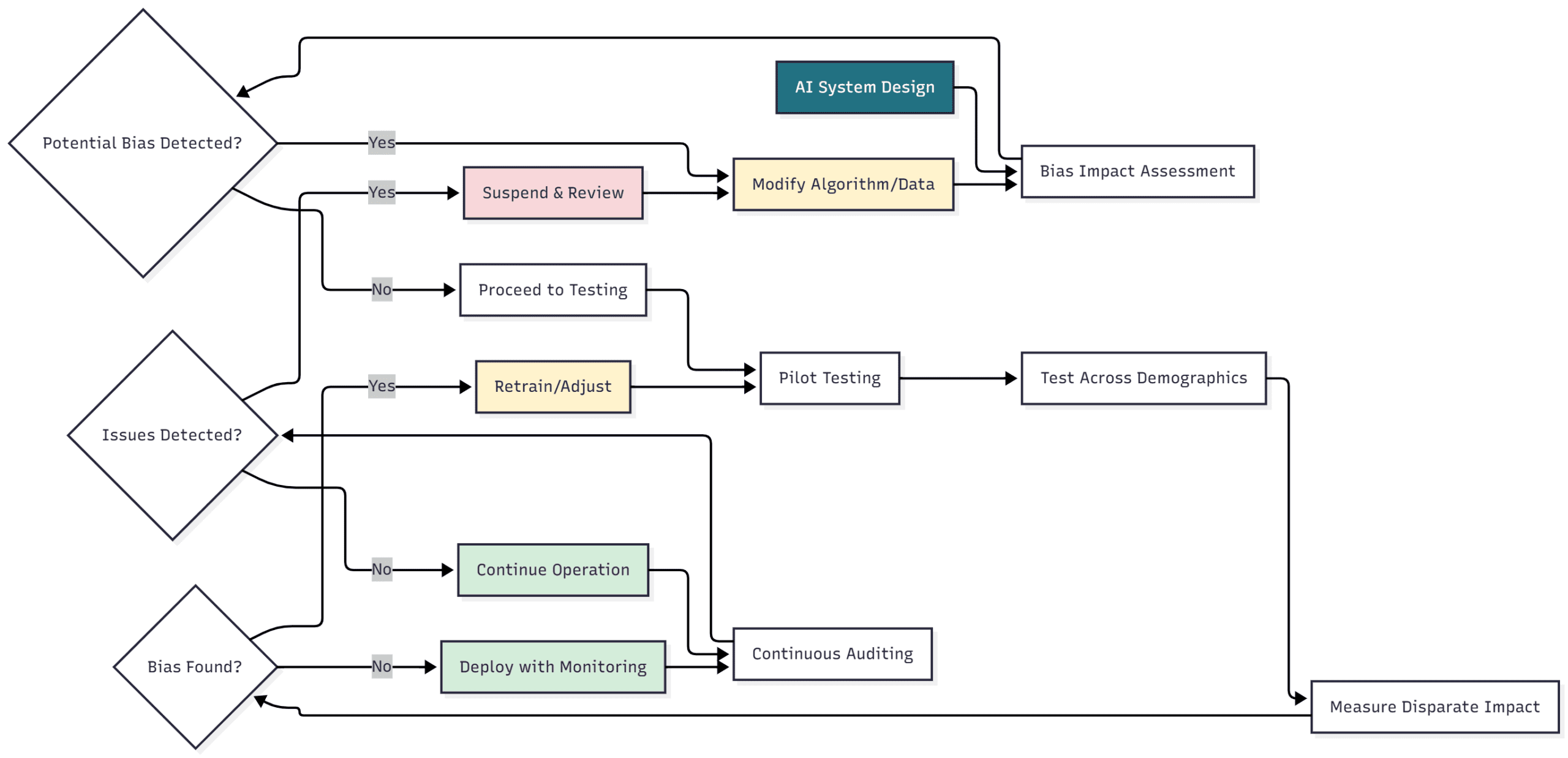

Challenges and Risks

While AI agents bring remarkable opportunities to improve public service delivery, they also introduce a host of challenges and risks that must be navigated carefully. These range from technical issues like data quality and system reliability, to ethical and societal concerns like bias, transparency, privacy, and the potential erosion of human accountability. Governments implementing AI in governance are learning that success is not just about deploying technology, but about doing so in a way that maintains public trust and upholds rights. In this section, we’ll examine some key challenges: data and bias problems, lack of transparency (the “black box” issue), the digital divide and accessibility, and governance/ethical oversights. Each challenge will be illuminated with real examples where possible, to ground the discussion in reality. We will also reflect on how these risks temper the enthusiasm around AI agents with sober responsibility.

Data Bias and Fairness: AI systems are only as good as the data and rules that shape them. In public services, much of the data reflects existing societal biases or historical inequalities. If an AI agent is trained on such data without correction, it can end up perpetuating or even amplifying discrimination. We have already seen worrisome instances of this. In the Netherlands, a scandal erupted when an algorithm used by the Tax Authority to detect welfare fraud in childcare benefits was found to be systematically biased against people with second nationalities or immigrant backgrounds[55][56]. The algorithm marked any non-Dutch citizen or even those with a foreign-sounding name as higher risk. As a result, thousands of parents (many of whom were from ethnic minorities) were wrongly flagged as fraudsters, had their benefits cut, and were subjected to invasive investigations[58]. Innocent families were plunged into financial hardship and trauma – an outcome opposite to the welfare system’s intent. The public outcry led to the resignation of the government in 2021 and a stark lesson that algorithmic bias can have devastating human costs.

Similar issues cropped up elsewhere in Europe. Sweden’s Social Insurance Agency used an AI to predict fraud in sick leave and benefits. Investigative journalists found that the model discriminated against women, migrants, and those with lower income or education levels – labeling them as higher fraud risks disproportionately[59][60]. In other words, the AI mirrored and reinforced societal biases that perhaps those groups are “suspect,” which is not a valid or fair assumption. In Austria, an employment agency’s algorithm for ranking unemployed persons by job market reintegration likelihood drew criticism for potentially channeling resources away from those who needed them most (like older workers or those with care responsibilities) – effectively an automated form of profiling that could exacerbate inequality.

These examples underscore that fairness is a paramount concern. AI agents need to be audited for bias regularly, especially in high-stakes contexts like social assistance decisions. If an AI denies someone’s benefit or opportunity, that person deserves to know why and whether it was fair. As one advocate put it, governments have been rushing to AI without proper testing, and thus “reinforcing systemic issues and bias”[52]. To address this, some countries are establishing guidelines: for instance, the U.S. has proposed that any AI used by the government that affects people’s rights should undergo equity assessments and include human oversight for important decisions[61]. In fact, after these incidents, the Netherlands and others have increased transparency requirements – making agencies publish details about algorithms they use, and in some cases outright banning algorithmic risk-scoring that lacks proper safeguards.

AI Bias & Fairness: Warning System

Learning from failures and successes to build trustworthy AI systems in public service

Critical Alert: AI Bias Can Cause Severe Harm

Algorithmic bias in public services has led to wrongful denial of benefits, discriminatory targeting, and government crises. These are not theoretical risks—they are documented failures affecting thousands of real people.

Key Lessons for Trustworthy AI

Fairness Implementation Framework

Transparency and the “Black Box”: Many AI models, especially those based on machine learning, are complex and not easily interpretable. This can lead to a situation where even the agency using the AI doesn’t fully understand how it arrived at a decision. Such opaqueness is problematic in governance. Citizens have a right to an explanation – why was my application denied? Why did I get selected for an audit? If the answer is “the computer said so and we’re not sure why,” that’s unacceptable. The lack of transparency not only frustrates citizens but also hampers accountability. Who is responsible for an AI’s decision? Is it the software vendor, the government agency, or no one (which shouldn’t be the case)?

One illustrative case: Spain’s system for screening energy subsidy applicants (called BOSCO) was found to have at least two major design flaws that caused it to wrongly reject eligible people (like certain widows on pensions)[62]. When a civic tech organisation (Civio) asked for the source code to investigate, they had to fight legally for access[63]. Such lack of openness meant that for a long time people were denied aid and couldn’t properly challenge it because the rules were hidden in code. Civio was eventually invited to present the case to the Supreme Court, highlighting the push for algorithmic transparency in public services[63]. The principle emerging is that if an AI algorithm has a significant impact on citizens, its workings should be open to scrutiny – at least by oversight bodies if not publicly (though publicly available code is ideal for trust). In some jurisdictions, like New York City, laws now require government-used algorithms to be made transparent and audited for bias.

However, transparency isn’t just about code availability; it’s also about understandability. Governments might need to invest in technology that provides explainable AI – systems that can output a rationale for their decisions in plain language. For instance, if an AI denies a loan or benefit, it might produce an explanation: “Application denied because income (\$X) is below required threshold \$Y and documents A, B, C were missing.” Or an AI system that triages health cases might explain: “Patient categorized as low-risk because symptoms reported match mild criteria and no danger signs were present.” These kinds of explanations are crucial for trust and for people to be able to contest decisions. It also helps agency staff to catch errors – if an explanation seems off, a human can double-check.

Reliability and Technical Limitations: AI agents can fail in mundane ways too – bugs, outages, adversarial inputs, you name it. A facial recognition system at an airport might go down and suddenly all passengers have to be processed manually, causing chaos. Or a machine translation bot might hilariously (or offensively) mistranslate a government message in another language, leading to confusion. With AI, there is also the risk of automation complacency – humans trusting the AI too much and not catching its mistakes. Imagine a social worker who assumes the system’s risk score is always right and neglects to apply her own judgment, or a doctor who over-relies on an AI’s diagnosis suggestion. If the AI is wrong and the human doesn’t double-check, the error propagates.

In critical systems, reliability is a life-and-death issue (think of AI in ambulance dispatch or disaster response). Thus, robust testing (as discussed in earlier chapters on validation) is key before deployment. Governments need to perform stress tests, simulate worst-case scenarios, and have backup plans (e.g., quickly switching to manual mode) if the AI tool fails. Regular audits for accuracy drift are important – an AI model might perform well on last year’s data but then degrade as patterns change (for example, fraud tactics evolve, or a new type of health condition emerges).

Digital Divide and Accessibility: Not everyone can equally access AI-powered services. This is a fundamental challenge: those who lack internet or devices, or have low literacy (digital or actual literacy), could be left out of the AI revolution in public services. The very people who often rely on government help – the poor, the elderly, rural communities – might be the ones with patchy access to digital tools. If a welfare application goes online with an AI chatbot and local offices close down, a farmer who has never used a computer might struggle to get aid. Similarly, an AI education tool might benefit urban students with good connectivity more than rural students with no Wi-Fi.