Executive Summary

This research paper provides a comprehensive analysis of Albania’s journey toward European Union membership, with a particular focus on assessing the likelihood of successful accession by 2030. Drawing on the latest political, economic, and institutional developments, the paper examines Albania’s progress in meeting EU accession criteria, the challenges it faces, and the complex dynamics of the EU enlargement process itself.

Albania has made significant strides in its EU accession process, opening 24 out of 33 negotiation chapters and implementing substantial reforms, particularly in the judiciary and anti-corruption areas. The country enjoys strong public support for EU membership (86.5%) and has maintained consistent political commitment to the European integration agenda across multiple governments.

However, Albania continues to face substantial challenges, including judicial capacity issues, persistent corruption, political polarization, and economic competitiveness concerns. These domestic challenges are compounded by the complexities of the EU enlargement process itself, which has been characterised by shifting criteria, inconsistent application of standards, and the influence of geopolitical considerations over technical readiness.

The research finds that while Albania’s official target of EU membership by 2030 is ambitious, it remains within the realm of possibility if reform momentum is maintained and the EU remains committed to the enlargement process. The most likely scenario appears to be a slight delay beyond 2030, with accession more probable in the 2031-2033 time frame. Alternative scenarios, including various forms of phased integration or regional arrangements, may emerge if full membership proves unattainable within this time frame.

The paper concludes that Albania’s EU accession prospects will depend on a complex interplay of domestic reform implementation, EU internal dynamics, and broader geopolitical considerations. The coming 2-3 years will be critical in determining which scenario prevails, with both Albania and the EU facing important choices that will shape the future of European integration in the Western Balkans.

1. Introduction

1.1 Research Context and Objectives

The Western Balkans’ integration into the European Union represents one of the most significant geopolitical projects of the early 21st century. For Albania, EU membership has been a consistent strategic priority since the fall of communism, representing both a return to the European family of nations and a pathway to economic prosperity and democratic consolidation.

This research paper aims to provide a comprehensive and critical assessment of Albania’s progress toward EU membership, with a particular focus on evaluating the likelihood of successful accession by 2030. The analysis examines Albania’s current political, economic, and institutional landscape; the status of accession negotiations; public and political support for membership; key challenges to accession; and the dynamics of the EU enlargement process itself, including claims of double standards in the treatment of candidate countries.

The research is guided by several key questions:

- What is Albania’s current state of readiness for EU membership across political, economic, and institutional dimensions?

- How has Albania progressed in its accession negotiations, and what benchmarks have been met?

- What are the primary challenges to Albania’s EU accession, both domestic and external?

- Does the EU apply double standards in its enlargement process, particularly regarding Albania and the Western Balkans?

- What are the realistic scenarios for Albania’s EU membership by 2030, and what factors will determine which scenario prevails?

1.2 Methodology and Sources

This research employs a mixed-methods approach, combining qualitative analysis of primary and secondary sources with quantitative assessment of economic and public opinion data. The analysis draws on a diverse range of sources to ensure comprehensive coverage and triangulation of findings:

- Official documents: European Commission progress reports, European Council conclusions, Albanian government strategies and reports

- Economic data: World Bank indicators, European Commission economic assessments, Albanian national statistics

- Public opinion research: Surveys on EU support in Albania and attitudes toward enlargement in EU member states

- Expert analyses: Reports from think tanks such as the European Council on Foreign Relations, Carnegie Europe, and Balkan Insight

- Academic literature: Scholarly research on EU enlargement, democratization, and Western Balkan politics

- Media coverage: Recent reporting on political developments in Albania and EU enlargement dynamics

The research adopts a critical perspective, acknowledging the complex interplay of technical criteria and political considerations in the EU accession process. It seeks to provide a balanced assessment that recognises both Albania’s achievements and the significant challenges it continues to face.

1.3 Historical Context: Albania’s European Journey

Albania’s path to EU membership has been shaped by its unique historical trajectory. Following nearly five decades of isolation under one of Europe’s most repressive communist regimes, Albania began its democratic transition in the early 1990s. The country’s European aspirations were formalised in 2006 with the signing of the Stabilisation and Association Agreement, which entered into force in 2009.

Albania submitted its application for EU membership in 2009 and was granted candidate status in 2014 after implementing key judicial and public administration reforms. However, the opening of accession negotiations was delayed until 2020, with the first intergovernmental conference held in 2022, marking the formal start of negotiations.

This historical context is essential for understanding both Albania’s determination to join the EU and the particular challenges it faces in meeting accession criteria. The legacy of isolation, delayed democratic transition, and institutional weaknesses has created obstacles that continue to influence Albania’s European integration process.

2. Current Political and Economic Landscape in Albania

2.1 Political Developments and 2025 Elections

The political landscape in Albania has been characterised by both continuity and significant reform efforts in recent years. The 2025 parliamentary elections, held on May 11, resulted in a fourth consecutive term for Prime Minister Edi Rama’s Socialist Party (PS), which secured 74 seats in the 140-seat parliament. The Democratic Party (DP), led by Sali Berisha, obtained 59 seats, while smaller parties gained the remaining 7 seats.

The election campaign was dominated by EU accession issues, with Rama promising full EU membership by 2030 and the opposition criticising the government’s reform implementation while maintaining support for the European integration goal. International observers from OSCE/ODIHR noted improvements in the electoral process compared to previous elections but highlighted continuing concerns about vote-buying allegations and media imbalance.

The election results reinforced political continuity, with Rama’s government maintaining its focus on EU-oriented reforms. The new government’s program, presented to parliament in June 2025, identified EU accession as the top priority, with specific commitments to judicial reform, anti-corruption efforts, and economic development aligned with EU standards.

However, political polarization remains a significant challenge. The European Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee specifically highlighted “a high degree of political polarization” as a continuing obstacle to reform implementation. This polarization has affected parliamentary activities and delayed key appointments, creating institutional instability that complicates the EU accession process.

2.2 Economic Indicators and Growth Trajectory

Albania’s economy has demonstrated resilience and moderate growth in recent years, though significant challenges remain in achieving convergence with EU economic standards. According to the European Commission’s Spring 2025 Economic Forecast, Albania’s GDP growth is projected at 3.6% for 2025, above the EU average but below the rates needed for rapid economic convergence.

Key economic indicators present a mixed picture:

- GDP per capita: Approximately 31% of the EU average (2024), showing gradual convergence but remaining significantly below even the poorest EU member states

- Unemployment rate: 10.2% (Q1 2025), down from 11.5% in 2023 but still high, particularly among youth (22.8%)

- Foreign Direct Investment: €1.2 billion in 2024, representing 7.8% of GDP, with significant concentration in energy, telecommunications, and tourism sectors

- Public debt: 68.5% of GDP (2024), down from peak levels but still above the EU’s 60% reference value

- Inflation: 2.8% (April 2025), within the central bank’s target range

The European Commission’s 2024 Economic Reform Programme assessment noted Albania’s progress in macroeconomic stability but highlighted continuing structural weaknesses, including an oversized informal economy (estimated at 30-35% of GDP), skills mismatches in the labor market, and limited industrial diversification.

The implementation of the EU’s Growth Plan for the Western Balkans, launched in November 2023, has provided new momentum for economic development. Albania has received €400 million in the first phase of the plan, focused on infrastructure development, green transition, and digital transformation. The European Commission estimates that successful implementation of the Growth Plan could double the size of the Western Balkan economies within a decade.

2.3 Infrastructure Development and EU Alignment

Infrastructure development has been a priority area for Albania, with significant progress in transport, energy, and digital infrastructure, though substantial gaps remain compared to EU standards.

In the transport sector, the completion of key segments of the Adriatic-Ionian Highway has improved connectivity with neighbouring countries, while the ongoing modernization of the Durrës-Tirana railway line, supported by EU funding, represents a significant step in revitalising Albania’s railway network. The European Investment Bank has committed €150 million for the rehabilitation of the Vora-Hani i Hotit railway line, connecting Albania to Montenegro and the broader European railway network.

Energy infrastructure has seen substantial development, particularly in renewable energy. Albania has increased its renewable energy capacity, with hydropower providing over 95% of domestic electricity production. However, the European Commission has noted the need for diversification of energy sources and improved energy efficiency to meet EU standards. The Trans Adriatic Pipeline, operational since 2020, has positioned Albania as part of the Southern Gas Corridor, enhancing energy security and integration with European energy markets.

Digital infrastructure has improved significantly, with broadband coverage reaching 85% of households by early 2025. The government’s Digital Albania initiative, aligned with the EU’s Digital Agenda, has accelerated e-government services and digital skills development. However, the European Commission’s Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) assessment indicates that Albania still lags behind EU averages in digital skills and business digitisation.

While these developments represent important progress, Albania’s infrastructure still requires substantial investment to reach EU standards. The European Commission estimates that closing the infrastructure gap with the EU would require investments of approximately €15 billion over the next decade, highlighting the scale of the challenge ahead.

2.4 Institutional Capacity and Public Sector Reforms

Institutional capacity and public sector reforms have been central to Albania’s EU accession process, with mixed results across different areas.

The public administration reform, guided by the 2015-2022 and 2023-2030 strategies, has made progress in establishing a more professional civil service and improving service delivery. The implementation of the Information System for Human Resource Management has enhanced transparency in recruitment and promotion, while the expansion of e-government services has reduced administrative burdens and corruption opportunities. In March 2025, the World Bank approved additional support of €50 million for Albania’s Public Service Transformation project, focusing on digital government services and administrative simplification.

However, significant challenges remain. The European Commission’s 2024 report noted that “despite legislative improvements, implementation of civil service legislation remains uneven,” with political influence in appointments still a concern, particularly at local government levels. The administrative capacity to implement and enforce the EU acquis remains limited in many sectors, with particular weaknesses in environmental protection, food safety, and public procurement.

The territorial and administrative reform implemented in 2015, which reduced the number of local government units from 373 to 61, has improved efficiency but created challenges in service delivery in remote areas. The Cooperation and Development Institute’s Reform Tracker, launched in May 2025, indicates that only 42% of planned local governance reforms have been fully implemented, highlighting the implementation gap between formal adoption and practical application of reforms.

Transparency and accountability mechanisms have improved, with the strengthening of independent oversight institutions such as the High Inspectorate for the Declaration and Audit of Assets and Conflict of Interests (HIDAACI). However, the European Commission has noted that “the impact of anti-corruption measures remains limited,” with implementation gaps and resource constraints affecting the effectiveness of these institutions.

Overall, while Albania has established the necessary legal and institutional frameworks for a functioning public administration aligned with EU principles, the implementation of these frameworks remains inconsistent. The gap between formal structures and practical outcomes continues to be a significant challenge for Albania’s EU accession process.

3. Status of EU Accession Negotiations

3.1 Progress in Negotiation Chapters

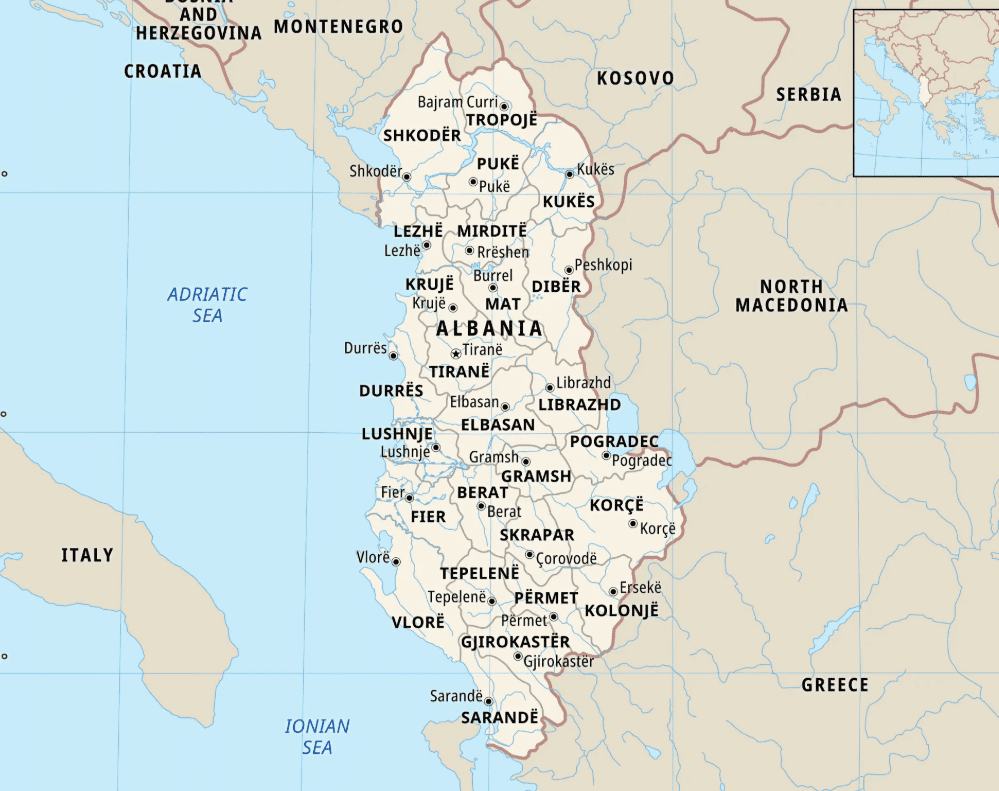

Albania’s EU accession negotiations have gained significant momentum since the formal opening of talks in July 2022. As of May 2025, Albania has opened 24 out of 33 negotiation chapters, organised in six clusters according to the revised enlargement methodology.

The most recent development was the opening of eight new chapters in Cluster 3 (Competitiveness and Inclusive Growth) during the Fifth Intergovernmental Conference on May 22, 2025. This followed the successful opening of Clusters 1 (Fundamentals) and 6 (External Relations) in October 2024 and March 2025, respectively.

The progress across clusters has been uneven:

- Cluster 1 (Fundamentals): All chapters opened, with significant progress in judiciary and fundamental rights (Chapter 23) and justice, freedom, and security (Chapter 24), though no chapters have been provisionally closed yet.

- Cluster 2 (Internal Market): Six out of eight chapters opened, with preliminary assessments indicating good alignment in free movement of goods but significant gaps in financial services and competition policy.

- Cluster 3 (Competitiveness and Inclusive Growth): All eight chapters opened in May 2025, with screening revealing moderate preparation in most areas.

- Cluster 4 (Green Agenda and Sustainable Connectivity): Four out of six chapters opened, with environment and climate change (Chapter 27) identified as particularly challenging.

- Cluster 5 (Resources, Agriculture, and Cohesion): Only two out of six chapters opened, reflecting the complexity of agricultural and regional policy alignment.

- Cluster 6 (External Relations): Both chapters opened, with good progress in foreign, security, and defense policy alignment.

While the opening of chapters represents important formal progress, the European Commission has emphasised that “opening of negotiations is just the beginning of a demanding process.” The Commission’s assessments indicate that Albania is moderately prepared in most areas, with significant work remaining to achieve full alignment with the EU acquis.

3.2 Judiciary, Anti-Corruption, and Human Rights

The areas of judiciary, anti-corruption, and human rights (primarily covered in Chapters 23 and 24) have been central to Albania’s accession process, with significant reforms implemented but substantial challenges remaining.

The judicial reform process, initiated with constitutional amendments in 2016, has been one of Albania’s most ambitious undertakings. The vetting process for judges and prosecutors, which concluded its first phase in 2024, resulted in the dismissal or resignation of 207 judges out of 400 vetted judges, while only 165 were confirmed in office. This process has significantly improved the integrity of the judiciary but created a severe shortage of judges, threatening the system’s functionality.

The Special Anti-Corruption Court and prosecution (SPAK) has emerged as a success story, demonstrating that impunity is diminishing. High-profile indictments, including those against a former president and the current mayor of Tirana, indicate that no one is beyond its oversight and jurisdiction. However, the European Parliament has emphasised the importance of ensuring “that the work of justice institutions, including SPAK, is not undermined.”

The judicial capacity crisis resulting from the vetting process has led to extreme delays in case resolution. The average length of resolution for civil cases increased from 250 days at the start of the vetting process to 1,250 days by its conclusion. Some administrative courts face average case resolution times of fourteen and a half years, while the Supreme Court’s backlog of thirty thousand cases means appeals may take over twelve years to resolve.

In the area of human rights, Albania has strengthened its legal framework, adopting comprehensive anti-discrimination legislation and establishing the Commissioner for Protection from Discrimination. However, implementation remains uneven, with particular concerns regarding the rights of minorities, especially Roma and Egyptian communities, and LGBTI+ persons. The European Commission has noted that “while the legal framework is largely aligned with European standards, implementation gaps persist.”

Media freedom remains a concern, with the European Parliament specifically highlighting the “need for continued reforms in media freedom” in its 2025 assessment. The Media Freedom Rapid Response mechanism documented 27 cases of threats or attacks against journalists in 2024, indicating continuing challenges in this area.

3.3 Market Reforms and Economic Criteria

Albania’s progress in meeting the economic criteria for EU membership has been steady but uneven across different areas.

The country has maintained macroeconomic stability, with sustained economic growth, moderate inflation, and a gradually declining public debt ratio. The banking sector remains well-capitalised and liquid, with non-performing loans reduced to 5.2% by the end of 2024. The Albanian lek has maintained stability against the euro, supporting economic predictability.

Albania has made significant progress in trade integration with the EU, which accounts for over 70% of its total trade. The implementation of the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA) and the Common Regional Market initiative has further enhanced regional economic integration. The adoption of EU standards and technical regulations has progressed, particularly in priority sectors such as food safety and consumer protection.

However, substantial challenges remain in establishing a fully functioning market economy capable of withstanding competitive pressure within the EU. The European Commission’s 2024 Economic Reform Programme assessment identified several structural weaknesses:

- Business environment: Despite improvements in business registration and licensing, regulatory burdens and legal uncertainty continue to hamper business development. The World Bank’s Doing Business indicators (last published in 2020) ranked Albania 82nd globally, below all EU member states.

- Informal economy: The large informal sector (estimated at 30-35% of GDP) distorts competition and reduces tax revenues, limiting the government’s capacity to invest in development priorities.

- Skills gap: Mismatches between education outcomes and labor market needs constrain productivity growth and innovation capacity. The European Commission has noted that “education and training systems do not sufficiently support skills development for a modern economy.”

- Productive investment: Investment remains concentrated in non-tradable sectors and infrastructure, with limited development of manufacturing and high-value-added services that could enhance export competitiveness.

- State influence: While privatisation has advanced in most sectors, state influence in the economy remains significant, with concerns about competitive neutrality and the governance of state-owned enterprises.

The implementation of the Economic Reform Programme and the Growth Plan for the Western Balkans aims to address these structural challenges, but the European Commission has emphasized that “sustained implementation over the medium term is essential” to achieve meaningful convergence with EU economic standards.

3.4 EU Assistance and Monitoring Mechanisms

The EU has deployed substantial financial and technical assistance to support Albania’s accession process, with increasingly sophisticated monitoring mechanisms to track reform implementation.

Financial assistance through the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA III) for the 2021-2027 period amounts to approximately €500 million for Albania, focusing on rule of law, good governance, environmental protection, and socio-economic development. Additional support is provided through the Western Balkans Investment Framework, which has mobilised over €1 billion in grants and loans for strategic infrastructure projects in Albania since its establishment.

The Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans, launched in October 2020, and the subsequent Growth Plan for the Western Balkans, announced in November 2023, represent significant scaling up of EU financial support. These initiatives aim to boost economic growth, support the green and digital transitions, and enhance regional economic integration, with a potential to mobilise up to €6 billion for Albania over the next decade.

Monitoring mechanisms have evolved to provide more detailed and frequent assessments of reform implementation. The revised enlargement methodology introduced in 2020 emphasises the “fundamentals first” principle, with enhanced monitoring of rule of law reforms through rule of law expert missions, peer reviews, and impact indicators. The European Commission’s annual reports provide comprehensive assessments across all chapters of the acquis, while specific progress reports on rule of law issues are published twice a year.

Civil society organisations play an increasingly important role in independent monitoring, with initiatives such as the EU Integration Advocacy Groups providing alternative assessments of reform implementation. The Cooperation and Development Institute’s Reform Tracker, launched in May 2025, represents a significant advance in monitoring tools, providing real-time tracking of reform implementation across different sectors.

While these assistance and monitoring mechanisms have supported Albania’s progress, challenges remain in ensuring effective coordination and absorption of EU funds. The European Court of Auditors’ 2023 special report on EU support to the Western Balkans noted that “the effectiveness of EU assistance is hampered by weak administrative capacity and lack of political will to implement certain reforms,” highlighting the limitations of external support without strong domestic ownership.

4. Public and Political Support

4.1 Public Opinion on EU Membership

Albania demonstrates exceptionally strong public support for EU membership, with several key characteristics:

The latest annual survey by the Albanian Institute for International Studies reveals that 86.5% of Albanians would vote in favour of EU accession, with only 7% opposed. This support has increased by 6 percentage points compared to the previous year, demonstrating resilience and even growth in pro-EU sentiment despite delays in the accession process.

Albania maintains the highest support for EU membership among Western Balkan countries, with the survey authors noting that “Albania has the largest support factor among perception of population in the region.” For 57.5% of respondents, European integration is “very important” in their personal realm, while for another third it is “quite important but not a priority.” Only 6% attach no importance to the process.

The drivers of public support reveal both economic pragmatism and aspirational elements. The primary motivation for EU support is economic, with 38% expecting improved living standards and 18% anticipating new job opportunities. Approximately 13% expect either less corruption or more justice, indicating that EU membership is seen as a pathway to better governance.

However, there appears to be a significant misunderstanding about the integration process, with many Albanians viewing EU membership as bringing improvements (free and fair elections, functioning justice system, less corruption) that are actually prerequisites for accession rather than consequences of it. This misalignment of expectations could create challenges as the accession process continues.

Albanians maintain a realistic assessment of their country’s EU readiness. Nearly half (49.1%) believe Albania is not yet ready to join the EU, while only 30.1% believe it is ready. This suggests a pragmatic understanding of the country’s current status. Opinion is evenly split on whether the EU should grant membership before full readiness, with 38% saying it should not and 37.3% believing it should.

The majority of Albanians (68%) assess their country’s integration progress as either “average” or “little,” with only 13.4% seeing “substantial” progress. Timeline expectations vary, with 40% expecting EU accession by 2020 (a date that has now passed), while a third expected accession within two years (an unrealistic timeline). Only 3% believe Albania will never join the EU, a significant decrease from previous surveys.

4.2 Political Consensus and Party Positions

EU membership enjoys broad political consensus across the Albanian political spectrum, though tactical differences exist in approaches to the integration process.

Prime Minister Edi Rama has made EU membership by 2030 a central campaign promise and governing priority, with his electoral victory in 2025 reinforcing this mandate. The government’s strategic documents consistently identify EU integration as the top national priority, with specific commitments to implementing the reforms required for accession.

The opposition Democratic Party under Sali Berisha, while critical of the government’s reform implementation, maintains a pro-EU stance. Berisha has argued that “Albania is not yet ready for EU membership” but supports the goal itself, focusing criticism on the pace and quality of reforms rather than the objective of EU accession.

Smaller political parties, including the Socialist Movement for Integration and the Social Democratic Party, also support EU membership, creating a rare national consensus around this strategic objective. This consensus has enabled the passage of key EU-related legislation, often with cross-party support, particularly for constitutional amendments related to judicial reform.

The political elite across parties maintains a pro-EU stance, with disagreements centred on implementation approaches and timelines rather than the ultimate objective. This consensus provides political stability for the EU integration process, ensuring continuity regardless of electoral outcomes.

The high public support provides political cover for potentially painful reforms, with politicians able to justify difficult changes as necessary for EU accession. However, the primarily economic expectations driving this support, combined with misunderstandings about the sequencing of reforms and benefits, create potential vulnerabilities in sustaining momentum through a lengthy accession process.

4.3 Regional Partnerships and Context

Albania’s EU aspirations exist within a broader framework of international relationships and regional dynamics.

The EU continues to lead the list of Albania’s strategic partners, reflecting alignment with European integration goals. The United States closely follows the EU as a strategic partner, indicating Albania’s balanced approach to Western alliances. Albania’s NATO membership since 2009 has reinforced its Western orientation and security integration.

Albania’s EU path is increasingly viewed in the context of broader Western Balkan integration, with Albania and Montenegro now explicitly mentioned as potential first entrants from the region. Albania has surpassed Serbia in opening negotiation chapters (24 vs. 22), positioning itself as one of the most advanced Western Balkan candidates alongside Montenegro.

Regional cooperation has evolved through various frameworks, including the Berlin Process, the Regional Cooperation Council, and more recently, the Open Balkan Initiative. Launched in 2021 by Albania, Serbia, and North Macedonia, the Open Balkan Initiative aims to enhance economic cooperation and free movement among member states. While this initiative has raised debates over whether it complements or undermines EU-led processes, Albanian officials have consistently presented it as complementary to EU integration.

Albania’s relations with neighboring countries have generally improved, though challenges remain. Relations with North Macedonia have strengthened through joint initiatives, including coordinated EU accession efforts. Albania has been a strong supporter of Kosovo’s international recognition and integration efforts, though this has complicated relations with Serbia. Relations with Greece have improved, though property rights issues for the Albanian minority in Greece and maritime border delimitation remain unresolved.

The regional context presents both opportunities and challenges for Albania’s EU path. On one hand, regional cooperation initiatives demonstrate Albania’s commitment to stability and integration, aligning with EU expectations. On the other hand, unresolved regional issues, particularly between Serbia and Kosovo, create potential complications for the entire Western Balkan accession process.

5. Challenges to Accession

5.1 Corruption and Organised Crime

Corruption and organised crime remain among the most significant challenges to Albania’s EU accession, despite notable progress in establishing anti-corruption frameworks and institutions.

Corruption continues to be “a serious concern across all levels of government,” according to multiple assessments. Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index ranked Albania 104th globally in 2024, the lowest among EU candidate countries and significantly below all EU member states. The European Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee specifically highlighted the need for “consolidating anti-corruption reforms” as a key priority.

The establishment of specialized anti-corruption institutions, particularly the Special Anti-Corruption Structure (SPAK), has demonstrated progress in high-level corruption cases. SPAK has pursued investigations against prominent political figures, including a former president and the current mayor of Tirana, indicating that no one is beyond its jurisdiction. However, the European Parliament has emphasized the importance of ensuring “that the work of justice institutions, including SPAK, is not undermined.”

While these high-profile cases represent important symbolic steps, systemic corruption remains pervasive. Petty corruption affects citizens’ daily interactions with public services, particularly in healthcare, education, and local administration. The European Commission’s 2024 report noted that “corruption remains prevalent in many areas and continues to be a serious concern,” highlighting the gap between institutional developments and practical outcomes.

Organized crime presents interconnected challenges, with Albanian criminal groups expanding their operations across Europe. Europol’s 2024 Serious and Organised Crime Threat Assessment identified Albanian criminal networks as “highly adaptable and entrepreneurial,” with significant involvement in drug trafficking, human trafficking, and money laundering. The European Commission has noted progress in combating organised crime, with increased seizures of criminal assets and international police cooperation, but emphasised that “sustained results in the fight against organised crime networks require systematic financial investigations and asset confiscation.”

The implementation gap between formal structures and practical outcomes remains a significant challenge. While Albania has established the necessary legal and institutional frameworks for fighting corruption and organised crime, the implementation of these frameworks remains inconsistent. The European Commission has emphasised the need for “a more proactive approach to investigating and prosecuting corruption at all levels,” highlighting the importance of moving beyond institutional development to achieve tangible results.

5.2 Judiciary Independence and Efficiency

The judicial system in Albania presents a complex picture of significant reform achievements alongside serious functional challenges that threaten to undermine these gains.

The judicial reform process, initiated with constitutional amendments in 2016, has fundamentally transformed Albania’s judicial governance system. The establishment of new institutions, including the High Judicial Council, the High Prosecutorial Council, and the Justice Appointment Council, has enhanced judicial independence by transferring powers from the executive branch to self-governing judicial bodies.

The vetting process for judges and prosecutors has been largely successful in its primary goal of removing corrupt judicial officials. Approximately 60% of Albanian judges failed the asset verification process, leading to the dismissal or resignation of 207 judges out of 400 vetted judges, while only 165 were confirmed in office. This process has significantly improved the integrity of the judiciary but created severe unintended consequences.

The most serious challenge is the judicial capacity crisis resulting from the vetting process. Albania now has around 250 judges effectively in office, down from over 400 before the vetting, creating one of the lowest ratios of judges per population among Council of Europe countries. This shortage has led to extreme delays in case resolution, with the average length for civil cases increasing from 250 days at the start of the vetting process to 1,250 days by its conclusion.

The Supreme Court’s backlog of thirty thousand cases means appeals may take over twelve years to resolve, effectively denying justice. Some administrative courts face average case resolution times of fourteen and a half years, according to official data from the Council of Justice. With a population of 2.5 million, Albania currently has around 120,000 pending cases in ordinary courts.

Public distrust in the judiciary has shifted from corruption concerns to inefficiency concerns. Simple cases, such as inheritance certificates, divorces, or disputes over rental contracts, are often delayed for many years, leading many Albanians to seek alternative conflict resolution methods. The right to presumption of innocence and initiatives for fighting criminality are at risk in criminal cases due to these delays.

The authorities have attempted to address these issues through a new judicial map that redistributes existing judges rather than increasing their number. This approach has involved closing courts in smaller towns and merging several others, raising serious concerns regarding access to justice, particularly for individuals living in remote areas. The logistical challenges and reorganisation efforts have exacerbated procedural delays, resulting in a decreasing clearance rate and an increasing backlog of cases.

While the School of Magistrates has increased its intake of new judges, the current quota of only ten new candidates for the next academic year is insufficient to address the shortage. The European Commission has emphasised the need for “urgent measures to address the backlog of cases and ensure timely access to justice,” highlighting the risk that judicial inefficiency could undermine the achievements of the reform process.

5.3 Electoral Integrity and Political Polarisation

Electoral integrity and political polarization remain significant challenges for Albania’s EU accession process, affecting both democratic functioning and reform implementation.

Despite improvements in the electoral framework, concerns about electoral integrity persist. The OSCE/ODIHR assessment of the 2025 parliamentary elections noted progress compared to previous elections but highlighted continuing issues with vote-buying allegations, pressure on public employees, and media imbalance. The European Parliament specifically noted that “the electoral reform must implement the recommendations of OSCE-ODIHR and the Venice Commission,” indicating that further improvements are needed.

Political polarization has been a persistent feature of Albanian politics, with the European Parliament highlighting “a high degree of political polarization” as a continuing challenge. This polarization hinders constructive dialogue and impedes progress on reforms, with parliamentary boycotts and institutional blockages occurring periodically. The European Parliament urged for “constructive and inclusive political dialogue” as Albania advances toward EU membership, indicating that the current political climate falls short of this standard.

The polarization extends beyond parliamentary politics to media and civil society, creating a divided public sphere that complicates consensus-building on key reforms. Media outlets are often aligned with political factions, limiting independent reporting and contributing to a fragmented information environment. The European Commission has noted that “political influence over media, particularly through advertising and other financial means, remains a concern.”

Electoral reform implementation remains incomplete despite amendments to the Electoral Code. Key recommendations from international organisations regarding campaign finance transparency, addressing vote-buying, and ensuring balanced media coverage have not been fully implemented. The European Commission has emphasised that “a track record of implementation of electoral reforms is essential for advancing on the EU path.”

The impact of polarization on reform implementation is particularly concerning for EU accession. While there is broad consensus on the goal of EU membership, tactical political considerations often override this strategic objective in day-to-day politics. The European Commission has noted that “political polarization continues to affect the pace and sustainability of reforms,” highlighting the need for more constructive political engagement to advance the EU integration agenda.

5.4 Freedom of the Press and Civil Society Space

Freedom of the press and civil society space in Albania present a mixed picture, with formal protections alongside practical limitations that raise concerns for EU accession.

Media freedom indicators show persistent challenges. Reporters Without Borders’ 2025 World Press Freedom Index ranked Albania 103rd globally, the lowest among EU candidate countries and below all EU member states. The European Parliament specifically highlighted the “need for continued reforms in media freedom” in its 2025 assessment.

Strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs) have emerged as a growing threat to media freedom. The Media Freedom Rapid Response mechanism documented 27 cases of threats or attacks against journalists in 2024, including several high-profile defamation lawsuits against investigative reporters covering corruption cases. The European Commission has emphasised that “intimidation of journalists, particularly those investigating corruption and organised crime, remains a serious concern.”

Media ownership concentration and transparency issues affect pluralism and independence. A small number of business groups control multiple media outlets, creating conflicts of interest and limiting editorial independence. The European Commission has noted that “the lack of transparency in media ownership and financing continues to hamper media pluralism,” highlighting the need for stronger regulatory frameworks.

Civil society organisations face both enabling and constraining factors. The legal framework for civil society is largely aligned with European standards, with the 2021 Law on Registration of Non-Profit Organisations simplifying registration procedures. However, practical challenges include limited financial sustainability, with high dependence on international donors, and occasional hostile rhetoric from political figures toward civil society organisations critical of government policies.

Public consultation mechanisms have improved formally but remain limited in practice. While the Law on Public Notification and Consultation established requirements for stakeholder involvement in policy-making, the European Commission has noted that “consultation often remains formalistic, with insufficient time for meaningful input and limited feedback on how contributions are considered.” This limits civil society’s ability to influence policy development effectively.

The role of civil society in the EU accession process has grown, with initiatives such as the EU Integration Advocacy Groups providing independent monitoring of reform implementation. However, the European Commission has emphasised the need for “more systematic involvement of civil society in the reform process,” indicating that current engagement falls short of EU expectations.

6. EU Enlargement Process and Double Standards

6.1 Shifting Goalposts and Conditionality

The evolution of EU accession criteria reveals patterns of expanding and shifting requirements that have significant implications for Albania’s accession prospects.

The scope of “fundamentals” has expanded considerably over time, with new requirements added to chapters 23 and 24 that were not applied to previous enlargement rounds. While the Copenhagen criteria established in 1993 remain the formal basis for accession, their interpretation and application have evolved substantially. The “fundamentals first” approach introduced in 2020 has further emphasised rule of law requirements, creating a more demanding process than that faced by earlier entrants.

The introduction of “balancing clauses,” including regional integration efforts and the normalization of relations between neighbours, represents a significant expansion of criteria beyond the traditional acquis. The International Centre for Defence and Security notes that these considerations “have appeared alongside the traditional ‘merits-based’ approach but seem to be applied to the detriment of the very fundamentals the EU professes to uphold.”

The gap between formal procedural advancement and substantive reform implementation creates challenges in assessing progress. While Albania has opened 24 out of 33 negotiation chapters, independent assessments suggest a less optimistic reality. The ICDS observes that “various independent studies have shown that no candidate state is anywhere near completing the course purely on merit,” indicating a disconnect between formal advancement and actual readiness.

The European Commission’s assessment methodology lacks transparency, with the ICDS noting that “the lack of transparency over the rating of progress serves as a cover to (geo)politically spin the conclusions.” This opacity enables inconsistent application of criteria and creates difficulties for candidate countries in understanding exactly what is required for advancement.

New requirements are sometimes applied retroactively to countries already in the process, creating frustration and perceptions of unfairness. As Blue Europe notes, EU-imposed conditionalities often feel more like “moving goalposts” than a clear path toward membership. This perception is particularly strong in Albania, where the opening of accession negotiations was delayed multiple times despite the country meeting previously established conditions.

The 2007 accession of Bulgaria and Romania, despite significant ongoing corruption and rule of law concerns, established a precedent of political decisions overriding technical readiness. This precedent continues to influence perceptions of fairness in the current enlargement process, with Western Balkan countries questioning why similar flexibility is not applied to their cases.

6.2 Comparative Analysis: Bulgaria, Romania, and Ukraine

Comparing Albania’s accession process with those of Bulgaria, Romania, and Ukraine reveals significant disparities in the application of criteria and the pace of integration.

Bulgaria and Romania joined the EU in 2007 despite significant ongoing concerns about corruption and judicial independence. The European Commission’s final monitoring reports before accession acknowledged serious deficiencies in both countries, yet political momentum for enlargement prevailed over technical readiness concerns. This decision led to the establishment of the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism (CVM) to monitor progress after accession, a unique arrangement that highlighted the exceptional nature of their entry.

The contrast with Albania’s experience is striking. Despite implementing more comprehensive judicial reforms than either Bulgaria or Romania had achieved pre-accession, Albania faced repeated delays in opening negotiations. The vetting process for judges and prosecutors, unprecedented in scope among candidate countries, demonstrates Albania’s commitment to addressing judicial corruption, yet this has not translated into accelerated progress in the accession process.

Ukraine’s rapid advancement from application to candidate status (less than four months) and the opening of accession negotiations within two years represents an unprecedented acceleration of the process. While this reflects the extraordinary geopolitical context following Russia’s invasion, it contrasts sharply with Albania’s experience of waiting eight years between candidate status (2014) and the opening of negotiations (2022).

The European Commission’s assessment methodology appears to apply different standards across cases. For Ukraine, the Commission recommended candidate status while acknowledging that significant reforms were still needed, emphasising Ukraine’s “strong commitment” to European values. For Western Balkan countries, including Albania, the emphasis has been on demonstrated implementation and track records of results before advancing to the next stage.

Financial support also shows disparities. The Ukraine Facility provides €50 billion in support, while the Growth Plan for the Western Balkans allocates €6 billion for six countries combined. While the different contexts partially explain this disparity, the scale of difference raises questions about equal treatment.

These disparities have not gone unnoticed in Albania and other Western Balkan countries. As Blue Europe notes, “if the EU accelerates Ukraine’s membership while continuing to delay the WB, it could reinforce perceptions of double standards, fuelling frustration and greater political instability in the region.” This perception risks undermining reform momentum and public support for the EU integration process.

6.3 Bilateral Disputes and Veto Powers

The EU enlargement process is significantly affected by bilateral disputes and the veto powers of individual member states, creating vulnerabilities that technical merit alone cannot overcome.

The veto power of individual member states at multiple stages of the accession process creates opportunities for bilateral issues unrelated to accession criteria to block progress. North Macedonia’s experience with Greek and later Bulgarian vetoes exemplifies this problem, with the country’s progress held hostage to bilateral historical and identity disputes despite meeting technical requirements for advancement.

While Albania has not faced direct bilateral vetoes, it has been affected by the coupling of its accession path with North Macedonia’s, with delays to North Macedonia’s progress effectively blocking Albania as well until the EU decided to decouple the two countries’ processes in 2020. This experience highlights how even countries without direct bilateral disputes can be affected by the veto dynamics.

The EU’s institutional framework provides limited mechanisms to overcome member state vetoes in the enlargement process. Unanimity requirements for key decisions create multiple veto points, with the European Council, General Affairs Council, and individual national parliaments during the ratification process all able to block progress. The revised enlargement methodology attempted to address this by clustering negotiation chapters, but the fundamental veto power remains unchanged.

The politicisation of technical assessments further complicates the process. While the European Commission provides technical evaluations of candidates’ readiness, the final decisions remain political, with member states sometimes disregarding Commission recommendations based on domestic political considerations or bilateral issues. This creates unpredictability in the process and undermines its merit-based credibility.

The impact of these dynamics on Albania’s accession prospects is significant. Even if Albania successfully implements all required reforms, its progress could still be blocked by individual member states for reasons unrelated to its technical readiness. This reality creates strategic challenges for Albanian policymakers, who must balance domestic reform priorities with diplomatic efforts to address potential bilateral concerns with EU member states.

6.4 Cultural Bias and Enlargement Fatigue

Cultural factors and internal EU dynamics significantly influence the enlargement process, often in ways that disadvantage Western Balkan countries including Albania.

Implicit assumptions about which countries are “truly European” affect enlargement attitudes, with Western Balkan countries sometimes perceived as culturally distant despite their geographical location in Europe. Historical perceptions of the Balkans as a region of conflict and instability continue to shape attitudes toward enlargement, despite significant progress in regional cooperation and stability.

Albania’s majority-Muslim population may face implicit bias in predominantly Christian EU member states, though this is rarely acknowledged explicitly in official discourse. While only 14% of Albanians view the country’s religious composition as an important factor in EU accession, perceptions in some EU member states may be influenced by religious identity considerations, particularly in the context of broader debates about Islam in Europe.

Enlargement fatigue among EU member states creates additional hurdles for Albania’s accession timeline. Despite renewed rhetoric following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, enlargement fatigue persists among many member states. As Blue Europe notes, “actual integration progress has been slow, riddled with institutional hesitation and growing disillusionment among the WB states themselves.”

Public opinion toward enlargement in key member states creates political constraints for leaders, particularly in the context of rising populism and nationalism. Eurobarometer surveys consistently show limited public support for further enlargement in many Western European countries, with concerns about migration, economic costs, and institutional functioning frequently cited.

The EU’s focus on other challenges (economic issues, migration, security concerns) diverts attention and political will from the enlargement process. The multiple crises facing the EU in recent years, from the euro zone crisis to Brexit to the COVID-19 pandemic, have reduced the political bandwidth available for enlargement, despite its strategic importance.

A significant gap exists between enlargement rhetoric and practical implementation. The ICDS notes that “while symbolic gestures signal intent, tangible commitments are essential for maintaining momentum,” highlighting the gap between rhetoric and meaningful action. This rhetoric-reality gap contributes to what Blue Europe describes as a “credibility deficit,” with many in the region questioning “whether the EU genuinely intends to welcome new members or if enlargement is simply a tool used to maintain influence without genuine commitments.”

7. Predictions and Scenarios

7.1 Realistic Timeline for Albanian Membership

Based on the comprehensive analysis of Albania’s current status and the dynamics of the EU enlargement process, several scenarios emerge for Albania’s EU membership timeline:

Scenario 1: Successful Accession by 2030 (Optimistic)

This scenario, which aligns with the Albanian government’s official target, has a moderate probability (40-50%) and would require several key conditions:

- Albania maintains and accelerates its reform implementation, particularly in judiciary, anti-corruption, and public administration

- The EU’s strategic interest in stabilising its southeastern flank amid continued Russian aggression and Chinese influence leads to political prioritisation of Western Balkan integration

- Albania successfully implements the Growth Plan for the Western Balkans, achieving significant economic growth and convergence with EU standards

- The EU streamlines its decision-making processes for enlargement, reducing procedural delays and political vetoes

Under this scenario, Albania would complete all negotiation chapters by 2027, sign the Accession Treaty in 2028, complete the ratification process by 2029, and formally join the EU in 2030. This timeline has received cautious endorsement from EU officials, with European Council President Antonio Costa stating in May 2025 that “If Albania continues to deliver at the same rate, it’s completely possible to join the European Union before 2030.”

Scenario 2: Delayed Accession (2031-2033) (Realistic)

This scenario has the highest probability (50-60%) and reflects the historical pace of negotiations, the complexity of remaining reforms, and the EU’s own internal dynamics:

- While Albania makes progress, implementation of complex reforms faces delays, particularly in addressing judicial efficiency and high-level corruption

- The EU’s internal reform process to prepare for enlargement takes longer than anticipated, delaying the final stages of accession

- The ratification process in EU member states encounters political obstacles, extending the post-negotiation period

- Albania makes progress but fails to fully close economic gaps with EU standards, requiring additional transition periods

Under this scenario, Albania would complete negotiation chapters by 2028-2029, sign the Accession Treaty in 2030, complete the ratification process by 2031-2032, and formally join the EU in 2032-2033. This timeline aligns with the assessment of many independent experts who view the 2030 target as ambitious but consider the early 2030s more realistic.

Scenario 3: Significant Delay or Alternative Arrangement (Pessimistic)

This scenario has a lower probability (10-20%) but cannot be dismissed given the complexities of the enlargement process:

- Political changes in Albania lead to backsliding on key reforms, particularly in judiciary independence and anti-corruption efforts

- Internal EU crises or political shifts lead to renewed enlargement skepticism and effective freezing of the accession process

- Individual EU member states use their veto power to block Albania’s progress for bilateral or domestic political reasons

- Global or regional economic crises significantly impact Albania’s economic convergence with EU standards

Under this scenario, Albania’s accession would be delayed indefinitely beyond 2035, or alternative arrangements such as a “privileged partnership” or multi-tiered EU membership might emerge. While less likely, this scenario highlights the vulnerability of the accession process to political and economic shocks.

7.2 Critical Success Factors

Several critical factors will determine which scenario prevails for Albania’s EU membership prospects:

Domestic Albanian Factors:

- Judicial Reform Completion: Albania must successfully address the judicial capacity crisis resulting from the vetting process, reducing case backlogs and improving efficiency while maintaining independence. This will require significant investment in recruiting and training new judges and modernising court administration.

- Anti-Corruption Effectiveness: SPAK must demonstrate continued effectiveness in high-level corruption cases while broader anti-corruption measures must show measurable impact across all levels of government. Particular attention is needed to preventive measures and addressing corruption in high-risk sectors such as public procurement, healthcare, and education.

- Political Stability: Maintaining political consensus on EU integration and reducing polarization will be essential for consistent reform implementation. This requires more constructive engagement between government and opposition on key EU-related reforms, potentially through enhanced parliamentary cooperation mechanisms.

- Economic Competitiveness: Albania must significantly improve its economic competitiveness, particularly in areas highlighted in negotiation chapters related to the internal market. This includes addressing the informal economy, improving the business environment, and enhancing export capacity in higher-value-added sectors.

- Administrative Capacity: Public administration reform must progress to ensure Albania has the institutional capacity to implement and enforce the EU acquis. This requires continued professionalization of the civil service, enhanced coordination mechanisms for EU integration, and improved policy implementation capacity.

European Union Factors:

- Enlargement Methodology: The EU must maintain its commitment to the revised enlargement methodology while ensuring that technical criteria are not overshadowed by political considerations. This includes more transparent assessment methodologies and consistent application of criteria across candidate countries.

- Internal Reform: The EU needs to implement internal reforms to prepare for enlargement, particularly in decision-making processes and budget allocations. The ongoing Conference on the Future of Europe and potential treaty reforms will significantly impact the EU’s absorption capacity for new members.

- Geopolitical Prioritisation: Western Balkan integration must remain a strategic priority for the EU despite competing challenges and crises. This requires sustained high-level political engagement and recognition of the geopolitical costs of delayed integration.

- Member State Alignment: Key EU member states must maintain political support for enlargement and refrain from using bilateral issues to block the process. This requires effective diplomatic engagement by both the EU institutions and Albania to address potential concerns before they become formal obstacles.

- Credible Conditionality: The EU must ensure that conditionality remains strict but fair, with clear and consistent criteria applied to all candidate countries. This includes avoiding the perception of double standards between different candidate countries and regions.

7.3 Alternative Scenarios and Arrangements

If full membership by 2030 proves unattainable, several alternative scenarios and arrangements might emerge:

Phased Integration:

- Sectoral Integration: Earlier integration into specific EU policy areas and programs before full membership, particularly in areas where Albania demonstrates readiness. This could include participation in the Single Market for specific sectors, enhanced cooperation in justice and home affairs, or integration into EU energy and transport networks.

- European Economic Area Plus: A structured relationship similar to the EEA but tailored to Western Balkan countries, providing most economic benefits of membership. This would offer deeper integration than the current Stabilization and Association Agreement while falling short of full political integration.

- Customs Union Enhancement: Deepening of the existing trade relationship through a more comprehensive customs union arrangement, potentially modeled on the EU-Turkey customs union but with enhanced provisions for services and regulatory alignment.

- “Everything But Institutions”: Access to the four freedoms and most EU policies without formal institutional representation, as a transitional arrangement. This approach would provide most practical benefits of membership while postponing the more politically sensitive aspects of institutional integration.

Regional Integration Pathways:

- Enhanced Open Balkan Initiative: Deepening of the Open Balkan Initiative as a stepping stone or complement to EU integration. This could involve expanding its scope beyond economic cooperation to include areas such as environmental protection, education, and cultural exchange.

- Western Balkan Common Market: Development of a more comprehensive regional economic integration framework with EU support, potentially modelled on the European Economic Community as a precursor to full EU integration.

- Differentiated Integration: A multi-speed approach to Western Balkan integration, with Albania potentially advancing ahead of other countries in the region. This would allow for recognition of Albania’s progress while acknowledging the different stages of readiness among Western Balkan countries.

- Strategic Partnership Framework: A formalised strategic partnership with enhanced political dialogue and cooperation mechanisms beyond the current association agreement. This could include observer status in certain EU institutions and enhanced participation in EU policy-making processes.

These alternative arrangements would not replace the goal of full EU membership but could provide intermediate steps and tangible benefits during what is likely to be a protracted accession process. They could also help maintain reform momentum and public support for European integration even if the timeline for full membership extends beyond 2030.

7.4 Implications for Albanian Policy

Based on these scenarios and critical factors, several implications emerge for Albanian policy-makers:

Strategic Prioritisation:

Given limited resources and political capital, Albania must strategically prioritize reforms that align with both EU requirements and domestic needs. This requires a more sophisticated approach to reform sequencing, focusing on areas where substantive progress is most achievable and impactful.

Key priorities should include:

- Addressing the judicial capacity crisis through accelerated recruitment and training of new judges

- Strengthening SPAK’s operational capacity while expanding anti-corruption efforts to preventive measures

- Implementing targeted economic reforms to enhance competitiveness in priority sectors

- Strengthening administrative capacity for EU acquis implementation, particularly in complex areas such as environment and agriculture

Expectation Management:

Albanian leaders must balance ambitious targets with realistic expectations to maintain public support through what is likely to be a protracted process. This requires more nuanced communication about the accession timeline and the sequencing of benefits and obligations.

Specific approaches should include:

- Emphasising the process benefits of reforms rather than focusing exclusively on the membership endpoint

- Highlighting tangible improvements in governance and economic opportunities resulting from EU-aligned reforms

- Providing realistic assessments of the challenges and timeline for accession

- Developing metrics to demonstrate progress beyond formal chapter openings and closings

Diplomatic Engagement:

Albania must complement domestic reforms with sophisticated diplomatic engagement to address potential political obstacles to accession. This requires a multi-dimensional approach targeting both EU institutions and individual member states.

Priority actions should include:

- Developing targeted diplomatic strategies for potentially skeptical EU member states

- Strengthening alliances with supportive member states, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe

- Enhancing engagement with the European Parliament and civil society in EU countries

- Leveraging Albania’s contributions to European security through NATO to strengthen its EU credentials

Regional Leadership:

Albania can potentially leverage its position as a regional leader in EU integration to advocate for more consistent application of criteria across candidate countries. This includes both bilateral engagement with neighbors and participation in regional initiatives.

Specific opportunities include:

- Strengthening the Open Balkan Initiative while ensuring its complementarity with EU integration

- Sharing reform experiences and best practices with other Western Balkan countries

- Advocating for a merit-based approach to enlargement that recognizes different levels of readiness among candidates

- Contributing to regional stability through constructive engagement in regional forums

By adopting this strategic approach, Albania can maximize its chances of achieving EU membership within a reasonable timeframe while ensuring that the reform process delivers tangible benefits for Albanian citizens regardless of the exact accession date.

8. Conclusion

8.1 Key Findings

This comprehensive analysis of Albania’s EU accession process reveals several key findings:

- Significant Progress Amid Persistent Challenges: Albania has made substantial progress in its EU accession process, opening 24 out of 33 negotiation chapters and implementing far-reaching reforms, particularly in the judiciary and anti-corruption areas. However, significant challenges remain, including judicial capacity issues, persistent corruption, political polarization, and economic competitiveness concerns.

- Strong Public Support but Expectation Gaps: Albania demonstrates exceptionally strong public support for EU membership (86.5%), providing a solid foundation for the country’s European integration efforts. However, the primarily economic expectations driving this support, combined with misunderstandings about the sequencing of reforms and benefits, create potential vulnerabilities in sustaining momentum through a lengthy accession process.

- Reform Implementation Gap: While Albania has established the necessary legal and institutional frameworks across multiple areas, the implementation of these frameworks remains inconsistent. The gap between formal structures and practical outcomes continues to be a significant challenge for Albania’s EU accession process.

- Double Standards in Enlargement Process: The EU enlargement process reveals significant tensions between its merit-based rhetoric and geopolitical reality. The treatment of different candidate countries demonstrates patterns of inconsistency that cannot be explained by objective criteria alone. The rapid advancement of Ukraine’s candidacy contrasts sharply with the protracted process for Western Balkan countries, including Albania.

- Geopolitical Considerations Increasingly Dominant: Geopolitical considerations increasingly override technical readiness in enlargement decisions, with security concerns taking precedence over traditional criteria. This creates both opportunities and challenges for Albania, which must navigate a complex landscape where technical merit alone is insufficient for advancement.

- Realistic Timeline Beyond 2030: While Albania’s official target of EU membership by 2030 remains within the realm of possibility, the most likely scenario appears to be a slight delay beyond 2030, with accession more probable in the 2031-2033 timeframe. This assessment is based on the historical pace of negotiations, the complexity of remaining reforms, and the EU’s own internal dynamics.

8.2 Implications for EU Enlargement Policy

The findings of this research have several important implications for EU enlargement policy:

- Credibility Challenge: The perceived application of double standards in the enlargement process threatens the EU’s credibility and leverage in the Western Balkans. To maintain its transformative power, the EU must ensure more consistent application of criteria across candidate countries and regions.

- Strategic Imperative: The geopolitical context, particularly Russia’s aggression in Ukraine and growing Chinese influence in the Western Balkans, creates a strategic imperative for the EU to accelerate the integration of countries like Albania that demonstrate clear Western orientation. Continued delays risk pushing Western Balkan countries to seek alternative partnerships.

- Methodology Refinement: The revised enlargement methodology introduced in 2020 represents progress but requires further refinement to balance rigorous conditionality with realistic expectations and clear incentives. Greater transparency in assessment methodologies and more consistent application of criteria are essential.

- Internal Reform Necessity: The EU’s ability to absorb new members depends on internal reforms to its decision-making processes and budget allocations. Without such reforms, the enlargement process risks creating expectations that cannot be fulfilled, further undermining the EU’s credibility.

- Phased Integration Value: Given the likely protracted timeline for full membership, the EU should develop more sophisticated phased integration approaches that provide tangible benefits and maintain reform momentum during the accession process. This could include earlier integration into specific policy areas and programs before full membership.

8.3 Recommendations for Albania

Based on the comprehensive analysis, several recommendations emerge for Albanian policy-makers:

- Judicial Capacity Crisis: Prioritize addressing the judicial capacity crisis resulting from the vetting process, with a focus on recruiting and training new judges, modernizing court administration, and implementing alternative dispute resolution mechanisms to reduce case backlogs.

- Anti-Corruption Effectiveness: Strengthen SPAK’s operational capacity while expanding anti-corruption efforts to preventive measures and addressing corruption in high-risk sectors such as public procurement, healthcare, and education.

- Political Dialogue: Develop more constructive engagement between government and opposition on key EU-related reforms, potentially through enhanced parliamentary cooperation mechanisms and depoliticized expert working groups.

- Economic Competitiveness: Implement targeted economic reforms to enhance competitiveness in priority sectors, address the informal economy, improve the business environment, and enhance export capacity in higher-value-added sectors.

- Administrative Capacity: Strengthen administrative capacity for EU acquis implementation, particularly in complex areas such as environment and agriculture, through continued professionalization of the civil service and improved policy implementation mechanisms.

- Strategic Communication: Develop more nuanced communication about the accession timeline and the sequencing of benefits and obligations, emphasizing the process benefits of reforms rather than focusing exclusively on the membership endpoint.

- Diplomatic Engagement: Complement domestic reforms with sophisticated diplomatic engagement targeting both EU institutions and individual member states, with particular attention to potentially skeptical member states.

- Regional Leadership: Leverage Albania’s position as a regional leader in EU integration to advocate for more consistent application of criteria across candidate countries and contribute to regional stability through constructive engagement in regional forums.

8.4 Final Assessment

Albania’s road to European Union membership represents a complex journey with both significant achievements and substantial remaining challenges. The country has demonstrated clear commitment to the European integration path, implementing far-reaching reforms and maintaining strong public and political support for EU membership.

However, the path ahead remains challenging, with domestic reform implementation gaps, EU enlargement complexities, and geopolitical uncertainties all influencing the timeline and prospects for accession. The official target of membership by 2030, while ambitious, remains within the realm of possibility if reform momentum is maintained and the EU remains committed to the enlargement process.

The most likely scenario appears to be a slight delay beyond 2030, with accession more probable in the 2031-2033 time frame. This assessment reflects both the progress Albania has made and the significant challenges it continues to face, as well as the complexities of the EU enlargement process itself.

Ultimately, Albania’s EU accession prospects will depend on a complex interplay of domestic reform implementation, EU internal dynamics, and broader geopolitical considerations. The coming 2-3 years will be critical in determining which scenario prevails, with both Albania and the EU facing important choices that will shape the future of European integration in the Western Balkans.

References

- European Commission. (2024). Albania 2024 Report. Brussels: European Commission.

- Albanian Institute for International Studies. (2025). Albanian Perceptions on EU Integration. Tirana: AIIS.

- European Parliament. (2025). Resolution on Albania’s Progress toward EU Membership. Brussels: European Parliament.

- International Centre for Defence and Security. (2025). A New but Ambiguous Momentum in EU Enlargement. Tallinn: ICDS.

- Blue Europe. (2025). Is the EU (Dream of) Enlargement in the Western Balkans Fading? Brussels: Blue Europe.

- Institut Jacques Delors. (2024). Albania’s steep road for accession by 2030. Paris: Institut Jacques Delors.

- Verfassungsblog. (2025). From Backlog to Breakdown: Albania’s Judiciary at a Cliff’s Edge. Berlin: Verfassungsblog.

- European Commission. (2024). Economic Reform Programme of Albania (2025-2027) – Commission Assessment. Brussels: European Commission.

- Transparency International. (2025). Corruption Perceptions Index 2024. Berlin: Transparency International.

- Cooperation and Development Institute. (2025). Reform Tracker: Monitoring Albania’s EU-related Reforms. Tirana: CDI.

- World Bank. (2025). World Bank Approves Additional Support to Advance Albania’s Public Service Transformation. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Reporters Without Borders. (2025). World Press Freedom Index 2025. Paris: RSF.

- OSCE/ODIHR. (2025). Final Report: Republic of Albania Parliamentary Elections, 11 May 2025. Warsaw: OSCE/ODIHR.

- European Council. (2025). Conclusions on Enlargement and Stabilisation and Association Process. Brussels: European Council.

- Europol. (2024). European Union Serious and Organised Crime Threat Assessment. The Hague: Europol.

Your insight matters! Leave your comments.

Leave a Reply